Page 109 - RAPTC Number 102 2018/19

P. 109

107

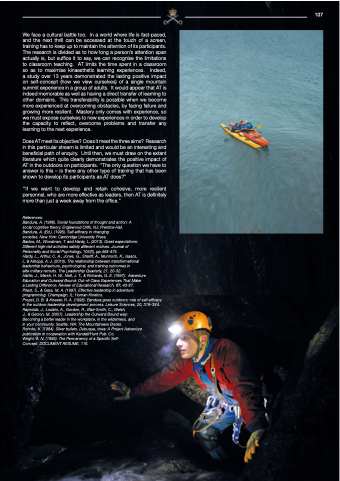

We face a cultural battle too. In a world where life is fast-paced, and the next thrill can be accessed at the touch of a screen, training has to keep up to maintain the attention of its participants. The research is divided as to how long a person’s attention span actually is, but suffice it to say, we can recognise the limitations to classroom teaching. AT limits the time spent in a classroom so as to maximise kinaesthetic learning experiences. Indeed, a study over 13 years demonstrated the lasting positive impact on self-concept (how we view ourselves) of a single mountain summit experience in a group of adults. It would appear that AT is indeed memorable as well as having a direct transfer of learning to other domains. This transferability is possible when we become more experienced at overcoming obstacles, by facing failure and growing more resilient. Mastery only comes with experience, so we must expose ourselves to new experiences in order to develop the capacity to reflect, overcome problems and transfer any learning to the next experience.

Does AT meet its objective? Does it meet the three aims? Research in this particular stream is limited and would be an interesting and beneficial path of enquiry. Until then, we must draw on the extant literature which quite clearly demonstrates the positive impact of AT in the outdoors on participants. ‘’The only question we have to answer is this – is there any other type of training that has been shown to develop its participants as AT does?’’

‘’If we want to develop and retain cohesive, more resilient personnel, who are more effective as leaders, then AT is definitely more than just a week away from the office.’’

References:

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A

social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (Ed.). (1995). Self-efficacy in changing

societies. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Barlow, M., Woodman, T. and Hardy, L. (2013). Great expectations:

Different high-risk activities satisfy different motives. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 105(3), pp.458-475.

Hardy, L., Arthur, C. A., Jones, G., Shariff, A., Munnoch, K., Isaacs,

I., & Allsopp, A. J. (2010). The relationship between transformational

leadership behaviours, psychological, and training outcomes in

elite military recruits. The Leadership Quarterly, 21, 20-32.

Hattie, J., Marsh, H. W., Neill, J. T., & Richards, G. E. (1997). Adventure Education and Outward Bound: Out-of-Class Experiences That Make

a Lasting Difference. Review of Educational Research, 67, 43-87.

Priest, S., & Gass, M. A. (1997). Effective leadership in adventure

programming. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Propst, D. B. & Koesler, R. A. (1998). Bandura goes outdoors: role of self-efficacy in the outdoor leadership development process. Leisure Sciences, 20, 319–344. Raynolds, J., Lodato, A., Gordon, R., Blair-Smith, C., Welsh,

J., & Gerzon, M. (2007). Leadership the Outward Bound way:

Becoming a better leader in the workplace, in the wilderness, and

in your community. Seattle, WA: The Mountaineers Books.

Rohnke, K. (1984). Silver bullets. Dubuque, Iowa: A Project Adventure

publication in cooperation with Kendall/Hunt Pub. Co.

Wright, A. N. (1996). The Permanency of a Specific Self-

Concept. DOCUMENT RESUME, 116.