Page 223 - Flaunt 171 - Summer of Our Discontent - PS

P. 223

SAY WHAT? A MARMOT?

The Extensive and Stylish History of Mask Making and Wearing in Times of Disease

Written by Michelle Varinata

Face masks are the new gold hoop earrings, the it-bag, the soup du jour. Just as essential as toilet paper, face masks of every kind—from chic printed cotton to disposable surgical paper— are starting to appear

more frequently in

our households and

on our feeds. Espe-

cially when the mask

is made with pure

gold.1 Worth more

than a gram of gold in

Indonesia2, and jolting

the stock market at

$9 billion on Etsy3,

it looks like the face

mask is not going to

go away even long af-

ter the pandemic ends.

However, like pandem-

ics, face masks are not

a new phenomenon.

be the source of the plague pandemic across Europe. The mask was often worn with a waxed coat and goat leather gloves9,

and accessorized with a rod used to touch the skin of plague

In the 13th centu-

ry, Marco Polo, an Ital-

ian explorer, observed

that the servants of

the Chinese Yuan em-

perors wore luxurious

face masks—scarf-

like design made

out of silk and gold

threads4—to prevent

their breath from

damaging the smell

and taste of the food5

they were preparing

and serving. This

mindset was linked to

the obsolete miasma

theory, where bad

odors were believed

to be the source of

diseases, like cholera

or the Black Plague.

In fact, the very silk

industry that fed mask

production, as well as

other global demands

for the luxury fiber,

came to terms with mias-

ma theory: production of

silk worms often meant

disease6, and miasma theory presumed disease the fault of bad odors. So, much like a Californian greets you in their living room, farmers burned incense for the silk worms in the hopes of good vibes and strong immunity.

Although it was a staple in the East, the Western world did not catch up to the face mask trend until Charles de Lorme,

a doctor, designed one in the 17th century for medical profes- sionals who were treating plague victims. With a bird-like face, the beaked mask stored theriac7—a potpourri-like mixture

of honey, cinnamon, viper flesh powder, camphor, mint, rose petals and myrrh to protect against miasma8, then believed to

victims. This mask, in combination with the medical smock we’re familiar with today, was inspired by the armor of soldiers, and the getup influenced the next generations of face masks around the world in later centu- ries.

In 19th century Japan, cloth masks were mass produced for miners, factory, and construction workers during the Meiji era. These face masks featured a brass mesh filter and two strings around the ears. Grad- ually, brass or metal was phased out with celluloid. Due to their costly price, celluloid masks were meant to be re-worn numerous times, especially if its coverings were made out of luxurious mate- rials such as velvet and leather10.

Alas, we’re all aware of folks out there who are not wearing masks by choice, and it’s not because they haven’t the coolest model on the block. It’s because they’ve forgotten

their history! In 1897, Johann von Miku- licz-Radecki, a Polish surgeon, proved in his

research that a surgical mask should consist of a layer of gauze11. That same year, Carl Fried- rich Flügge, a German

hygienist, argued that droplets from the nose and mouth were the cause of diseases12 spreading. A handful of years later, Chicago-based physician Alice Hamilton stated that surgeons should wear face masks13 after conducting research measuring the release of step bacteria in the company doctors and nurses when they perform surgery.

Five years after Hamilton made her study, Malaysia-born and Cambridge educated physician Wu Lien-Teh was asked by

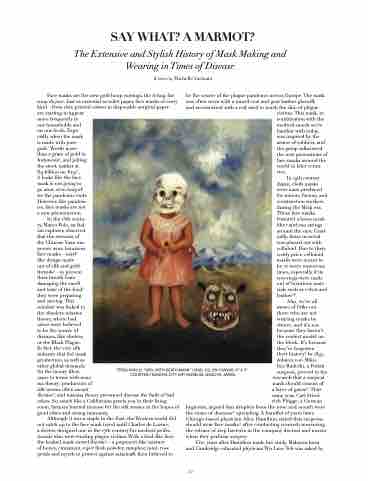

FRIDA KAHLO. “GIRL WITH DEATH MASK” (1938). OIL ON CANVAS. 6” X 4”. COURTESY NAGOYA CITY ART MUSEUM, NAGOYA, JAPAN.

223