Page 285 - Physics Coursebook 2015 (A level)

P. 285

Chapter 18: Gravitational fields

Figure 18.4 shows the Earth’s gravitational field

closer to its surface. The gravitational field in and

around a building on the Earth’s surface shows that the gravitational force is directed downwards everywhere and (because the field lines are parallel and evenly spaced) the strength of the gravitational field is the same at all points in and around the building. This means that your weight is the same everywhere in this gravitational field. Your weight does not get significantly less when you go upstairs.

field lines

MF Fm r

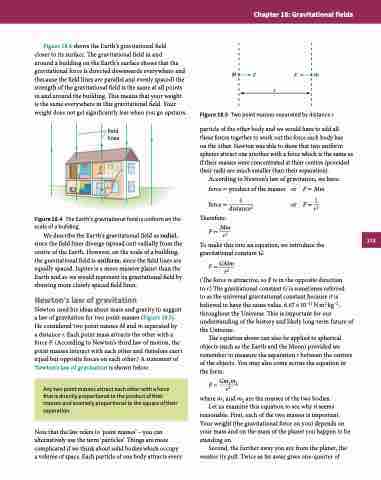

Figure 18.5 Two point masses separated by distance r.

particle of the other body and we would have to add all these forces together to work out the force each body has

on the other. Newton was able to show that two uniform spheres attract one another with a force which is the same as if their masses were concentrated at their centres (provided their radii are much smaller than their separation).

According to Newton’s law of gravitation, we have:

Figure 18.4 The Earth’s gravitational field is uniform on the scale of a building.

We describe the Earth’s gravitational field as radial, since the field lines diverge (spread out) radially from the centre of the Earth. However, on the scale of a building, the gravitational field is uniform, since the field lines are equally spaced. Jupiter is a more massive planet than the Earth and so we would represent its gravitational field by showing more closely spaced field lines.

Newton’s law of gravitation

Newton used his ideas about mass and gravity to suggest a law of gravitation for two point masses (Figure 18.5). He considered two point masses M and m separated by

a distance r. Each point mass attracts the other with a force F. (According to Newton’s third law of motion, the point masses interact with each other and therefore exert equal but opposite forces on each other.) A statement of Newton’s law of gravitation is shown below.

Note that the law refers to ‘point masses’ – you can alternatively use the term ‘particles’. Things are more complicated if we think about solid bodies which occupy a volume of space. Each particle of one body attracts every

force ∝ product of the masses or force ∝ 1 or

Therefore:

F ∝ Mm r2

To make this into an equation, we introduce the gravitational constant G:

F = GMm r2

(The force is attractive, so F is in the opposite direction

to r.) The gravitational constant G is sometimes referred

to as the universal gravitational constant because it is believed to have the same value, 6.67 × 10−11 N m2 kg−2, throughout the Universe. This is important for our understanding of the history and likely long-term future of the Universe.

The equation above can also be applied to spherical objects (such as the Earth and the Moon) provided we remember to measure the separation r between the centres of the objects. You may also come across the equation in the form:

F = Gm1m2 r2

where m1 and m2 are the masses of the two bodies. Let us examine this equation to see why it seems

reasonable. First, each of the two masses is important. Your weight (the gravitational force on you) depends on your mass and on the mass of the planet you happen to be standing on.

Second, the further away you are from the planet, the weaker its pull. Twice as far away gives one-quarter of

distance2

r2

F ∝ Mm F ∝ 1

Any two point masses attract each other with a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of their separation.

273