Page 336 - Geosystems An Introduction to Physical Geography 4th Canadian Edition

P. 336

300 part II The Water, Weather, and Climate Systems

35.0 32.5 30.0 27.5 25.0 22.5 20.0 17.5 15.0 12.5 10.0

7.5 5.0 2.5

38

32

27

21

16

10

4

0 –1

–7 –12 –18 –23 –29 –34 –40

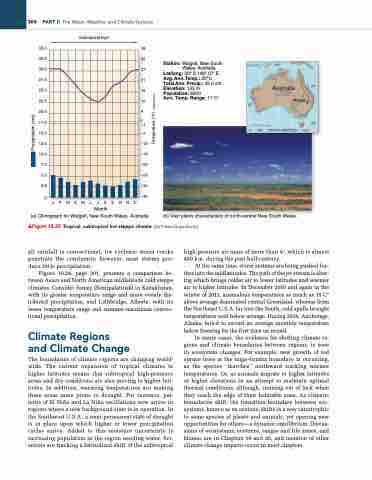

Station: Walgett, New South Wales, Australia

Lat/long: 30° S 148° 07′ E Avg. Ann. Temp.: 20°C Total Ann. Precip.: 45.0 cm Elevation: 133 m Population: 8200

Ann. Temp. Range: 17 C°

Subtropical high

0

JFMAMJJASOND

Month

(a) Climograph for Walgett, New South Wales, Australia.

(b) Vast plains characteristic of north-central New South Wales.

▲Figure 10.23 Tropical, subtropical hot steppe climate. [(b) Prisma/SuperStock.]

all rainfall is convectional, for cyclonic storm tracks penetrate the continents; however, most storms pro- duce little precipitation.

Figure 10.24, page 301, presents a comparison be- tween Asian and North American midlatitude cold steppe climates. Consider Semey (Semipalatinsk) in Kazakhstan, with its greater temperature range and more evenly dis- tributed precipitation, and Lethbridge, Alberta, with its lesser temperature range and summer-maximum convec- tional precipitation.

Climate Regions and Climate Change

The boundaries of climate regions are changing world- wide. The current expansion of tropical climates to higher latitudes means that subtropical high-pressure areas and dry conditions are also moving to higher lati- tudes. In addition, warming temperatures are making these areas more prone to drought. For instance, pat- terns of El Niño and La Niña oscillations now arrive in regions where a new background state is in operation. In the Southwest U.S.A., a semi-permanent state of drought is in place upon which higher or lower precipitation cycles arrive. Added to this moisture uncertainty is increasing population in the region needing water. Sci- entists are tracking a latitudinal shift of the subtropical

high-pressure air mass of more than 4°, which is almost 450 km, during the past half-century.

At the same time, storm systems are being pushed fur- ther into the midlatitudes. The path of the jet stream is alter- ing which brings colder air to lower latitudes and warmer air to higher latitudes. In December 2010 and again in the winter of 2013, anomalous temperatures as much as 15 C° above average dominated central Greenland, whereas from the Northeast U.S.A. far into the South, cold spells brought temperatures well below average. During 2014, Anchorage, Alaska, failed to record an average monthly temperature below freezing for the first time on record.

In many cases, the evidence for shifting climate re- gions and climate boundaries between regions, is seen in ecosystem changes. For example, new growth of red spruce trees at the taiga–tundra boundary is occurring, as the species “marches” northward tracking warmer temperatures. Or, as animals migrate to higher latitudes or higher elevations in an attempt to maintain optimal thermal conditions, although, running out of luck when they reach the edge of their habitable zone. As climatic boundaries shift, the transition boundary between eco- systems, known as an ecotone, shifts in a way catastrophic to some species of plants and animals, yet opening new opportunities for others—a dynamic equilibrium. Discus- sions of ecosystems, ecotones, ranges and life zones, and biomes are in Chapters 19 and 20, and mention of other climate change impacts occur in most chapters.

Australia Walgett

0 600 1200 KILOMETRES

130°

150°

30°

20°

40°

Precipitation (cm)

Temperature (°C)