Page 221 - Cooke's Peak - Pasaron Por Aqui

P. 221

government was concerned over the water situation in the area. Sometime in the fall, the railroad and

the federal government concluded a deal where, in return for use of up to half the water, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad would clean the spring and construct a retaining vessel to collect the water and pipe it to the station for use. The other half of the water would remain available for public consumption and for use at Fort Cummings. Reli- able estimates of the spring’s capacity indicated a potential yield of 50,000 gallons a day."

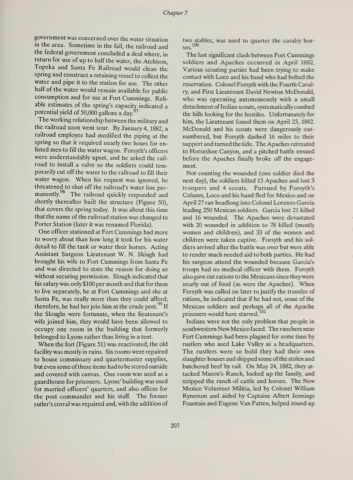

The working relationship between the military and the railroad soon went sour. By January 4, 1882, a railroad employee had modified the piping at the spring so that it required nearly two hours for en- listed men to fill the water wagon. Forsyth’s officers were understandably upset, and he asked the rail- road to install a valve so the soldiers could tem- porarily cut off the water to the railroad to fill their water wagon. When his request was ignored, he threatened to shut off the railroad’s water line per- manently. The railroad quickly responded and shortly thereafter built the structure (Figure 50), that covers the spring today. It was about this time that the name of the railroad station was changed to Porter Station (later it was renamed Florida).

One officer stationed at Fort Cummings had more to worry about than how long it took for his water detail to fill the tank or water their horses. Acting Assistant Surgeon Lieutenant W. N. Slough had brought his wife to Fort Cummings from Santa Fe and was directed to state the reason for doing so without securing permission. Slough indicated that his salary was only $100 per month and that for them to live separately, he at Fort Cummings and she at Santa Fe, was really more than they could afford; therefore, he had her join him at the crude post." If the Sloughs were fortunate, when the lieutenant’s wife joined him, they would have been allowed to occupy one room in the building that formerly belonged to Lyons rather than living in a tent.

When the fort (Figure 51) was reactivated, the old facility was mostly in ruins. Six rooms were repaired to house commissary and quartermaster supplies, but even some of these items had to be stored outside and covered with canvas. One room was used as a guardhouse for prisoners. Lyons’ building was used for married officers’ quarters, and also offices for the post commander and his staff. The former sutler’s corral was repaired and, with the addition of

two stables, was used to quarter the cavalry hor- 100

ses.

The last significant clash between Fort Cummings

soldiers and Apaches occurred in April 1882. Various scouting parties had been trying to make contact with Loco and his band who had bolted the reservation. Colonel Forsyth with the Fourth Caval- ry, and First Lieutenant David Newton McDonald, who was operating autonomously with a small detachment of Indian scouts, systematically combed the hills looking for the hostiles. Unfortunately for him, the Lieutenant found them on April 23, 1882. McDonald and his scouts were dangerously out- numbered, but Forsyth dashed 16 miles to their support and turned the tide. The Apaches retreated to Horseshoe Canyon, and a pitched battle ensued before the Apaches finally broke off the engage- ment.

Not counting the wounded (one soldier died the next day), the soldiers killed 13 Apaches and lost 3 troopers and 4 scouts. Pursued by Forsyth’s Column, Loco and his band fled for Mexico and on April 27 ran headlong into Colonel Lorenzo Garcia leading 250 Mexican soldiers. Garcia lost 21 killed and 16 wounded. The Apaches were devastated with 20 wounded in addition to 78 killed (mostly women and children), and 33 of the women and children were taken captive. Forsyth and his sol- diers arrived after the battle was over but were able torendermuchneededaidtobothparties. Hehad his surgeon attend the wounded because Garcia’s troops had no medical officer with them. Forsyth also gave out rations to the Mexicans since they were nearly out of food (as were the Apaches). When Forsyth was called on later to justify the transfer of rations, he indicated that if he had not, some of the Mexican soldiers and perhaps all of the Apache

101

prisoners would have starved.

Indians were not the only problem that people in

southwestern New Mexico faced. The ranchers near Fort Cummings had been plagued for some time by rustlers who used Lake Valley as a headquarters. The rustlers were so bold they had their own slaughter houses and shipped some of the stolen and butchered beef by rail. On May 24, 1882, they at- tacked Mason’s Ranch, locked up the family, and stripped the ranch of cattle and horses. The New Mexico Volunteer Militia, led by Colonel William Rynerson and aided by Captains Albert Jennings Fountain and Eugene Van Patten, helped round up

Chapter 7

207