Page 11 - 13_Bafta ACADEMY_Judi Dench_ok

P. 11

It was, now famously, a 19th Century painting titled Pollice Verso (translation: Thumbs Up) by a rather obscure French painter which first fired Ridley Scott to make Gladiator, eventu- al winner of Best Film at both the American and British Academy Awards last year.

When it came next to Hannibal, the prospect of tack- ling a sequel didn’t remotely con- cern him even though he shied away deliberately from ever being involved again in the suc- cessful film series he’d initiated years earlier with Alien.

The hook for Hannibal was “the density of the story and the characters.” Oh, and a chance finally to work with Anthony Hopkins.

In the case of his 13th and latest feature, Black Hawk Down, about the bloodily botched 1993 Battle of Mogadishu, a tale of heroic American failure in Somalia, the inspiration was rather more mundane though, in Scott’s case, equally as stimulat- ing: reporter Mark Bowden’s book of the same name.

Scott, 62, explained: “It’s a great document, an anatomy of what these guys [Rangers and Delta Force soldiers] can do. It consisted of first-hand interviews with the people involved and so it’s not sentimentalised at all.

“I loved the real-time story; filmmakers dream that drama can occur in such a contained way. The mission was meant to take thirty-nine minutes but actually lasted 18 hours, which we then filmed in two-and-a half hours.”

The decision to bring forward the release [from its original March date] of Scott’s film in the wake of September 11 and the subsequent intervention in Afghanistan provoked some sug- gestion of gung-ho exploitation.

Scott admits he first thought that events might conspire to “push the film way back... but on closer examination we all felt the film was so relevant. It posed ques- tions about whether we should

interfere, but it doesn’t give any answers at the end. I don’t think there are any answers... even after September 11.”

Critical reaction to the film has ranged from “takes its place on the very short list of the unfor- gettable movies about war” to the decidedly equivocal, “top marks for action, zero marks for the message.”

Gung-ho? Scott recoils: “I’ve honestly tried to make it dispas- sionately not because I’m not American but that’s the way the book was.”

Born and raised in the North East, where he first studied design and painting before graduating from the Royal Academy of Art, Scott eventually joined the BBC first as a production designer then as a director on episodic tel- evision like Adam Adamant Lives! and Z Cars.

After three years, he left to form his own company RSA which remains one of the world’s leading commercial production houses. Scott himself has directed more than two thousand com- mercials down the years.

Since making his rather belat- ed feature debut, at 38, in 1977 with The Duellists, Scott has aver- aged a film every two years.

This exquisite adaptation of a Conrad short story set during the Napoleonic Wars is full of the trademark style and detail which Scott would retain as his projects grew ever bigger and more ambitious.

Scott failed – some suggest unaccountably – to win the Best Director awards here and in Hollywood for Gladiator. But there was perhaps some consola- tion that no fewer than three of his films – Alien, Blade Runner and Gladiator itself (at number 6) – were included in the top forty of a network TV audience survey voting on the all-time 100 Best.

Blade Runner, at number 8, is an admitted “all-time favourite” of Scott’s younger brother, Tony, a prolific director in his own right with films like Top Gun, True

Romance and, most recently, Spy Game. And that, he added, was “regardless of the fact it’s Rid.”

Tony Scott was also asked recently about the fact that Ridley tended to get a better crit- ical reception than him. His reply was intriguing: “He gets that because I think his subject matter is aimed more towards posterity and I tend to be a little more rock ‘n’ roll. There’s a healthy compet- itive spirit between us.”

Might they ever co-direct? The older sibling chortles: “Never. It wouldn’t be possible. It’s not rivalry, it’s just we think in a totally different ways. Mind you, Spy Game’s great. Normally he’d choose material I’d never choose to do and vice-versa, but Spy Game I’d have done. We work together in business which is the way it should stay.

The Scotts have been part- ners in RSA for 38 years and jointly run their film production compa- ny, Scott Free, which is also suc- cessfully involved in prestigious TV drama like RKO 281 and current- ly, A Lonely War, dealing with Churchill’s wilderness years. They are also own Shepperton and Pinewood Studios as well as the special effects house, The Mill. Their joint contribution to British film was recognised with BAFTA’s Michael Balcon Award in 1994.

For Ridley Scott , whether as a hands-on producer and/or direc- tor, the “material” is everything: “I have no specific preconcep- tion of what I’m going to do next because it’s all to do with the material at hand right now.

“I don’t develop 40 projects, I’ve probably got four or five in the pipeline. There are still several genres I’d like to tackle, such as a musical, a Western and very early history (Alexander The Great). Basically I’ve got all those in process at the moment.

“What’s on paper is every- thing. Once you have that and it’s correct the rest,” he smiles, puffing his large cigar, “is rela- tively straightforward.”

Getting

the subject matter right is the key, director Ridley Scott tells

Quentin Falk

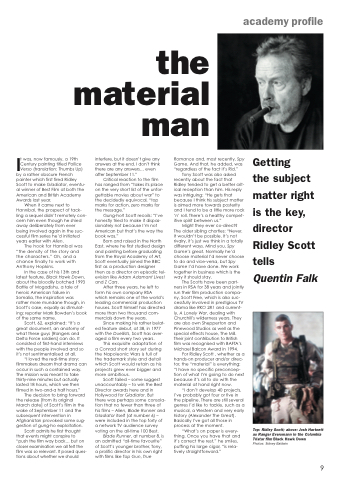

Top: Ridley Scott; above: Josh Hartnett as Ranger Eversmann in the Columbia Tristar film Black Hawk Down

Photos: Sidney Baldwin

the material man

academy profile

9