Page 14 - 24_Bafta ACADEMY_Anthony Minghella_ok

P. 14

academy profile

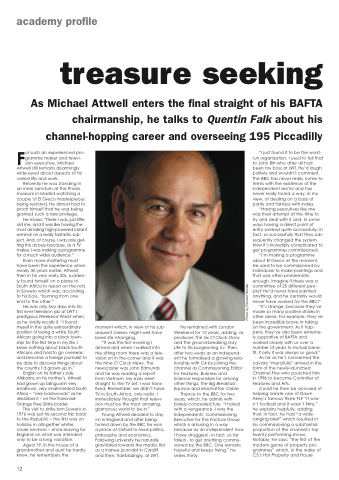

treasure seeking

As Michael Attwell enters the final straight of his BAFTA chairmanship, he talks to Quentin Falk about his channel-hopping career and overseeing 195 Piccadilly

For such an experienced pro- gramme maker and televi- sion executive, Michael Attwell still remains disarmingly wide-eyed about aspects of his varied life and work.

Recently he was standing in an inner sanctum at the Prado museum in Madrid watching a couple of El Greco masterpieces being restored. He almost had to pinch himself that he was being granted such a rare privilege.

He muses: “There I was, just little old me, and it was like having the most amazing high-powered instant seminar on a really fantastic sub- ject. And, of course, I was only get- ting this access because, as a TV maker, I was making a programme for a much wider audience.”

Even more shattering must have been the experience when, nearly 30 years earlier, Attwell, then in his very early 20s, sudden- ly found himself on a plane to South Africa to report on the riots in Soweto which was, according to his boss, “burning from one end to the other.”

He was only two days into his first ever television job at LWT’s prestigious Weekend World when, as he vividly recalls it, “I found myself in the quite extraordinary position of being a white South African going into a black town- ship for the first time in my life. I knew nothing about black South Africans and had to go overseas and become a foreign journalist to be able to discover things about the country I’d grown-up in.”

English on his father’s side, Afrikaans on his mother’s, Attwell had grown up bilingual in very smalltown, very small-minded South Africa – “very backwoods” as he describes it – on the Transvaal- Orange Free State border.

The visit to strife-torn Soweto in 1976 was just his second trip back to the Republic – the first was on holiday in altogether whiter, cosier environs – since leaving for England on what was intended only to be a long vacation.

Aged 19, in the house of a grandmother and aunt he hardly knew, he remembers the

moment which, in view of his sub- sequent career, might well have been life-changing.

“It was the first evening I arrived and when I walked into the sitting room there was a tele- vision on in the corner and it was the Nine O’Clock News. The newscaster was John Edmunds and he was reading a report from Vietnam. My eyes went straight to the TV set; I was trans- fixed. Remember, we didn’t have TV in South Africa, only radio. I immediately thought that televi- sion must be the most amazing, glamorous world to be in.”

Young Attwell decided to stay on in England and after being turned down by the BBC he won a place at Oxford to read politics, philosophy and economics. Following university he naturally gravitated towards the media, first as a trainee journalist in Cardiff and then, trail-blazingly, at LWT.

He remained with London Weekend for 10 years, adding, as producer, The Six O’Clock Show and the ground-breaking Gay Life to his burgeoning cv. Then, after two years as an independ- ent he formalised a growing rela- tionship with C4 by joining the channel as Commissioning Editor for Features, Business and Science responsible for among other things, The Big Breakfast, Equinox and Manhattan Cable.

Thence to the BBC for two years, which, he admits with barely-concealed fury, “I hated with a vengeance. I was the Independents’ Commissioning Executive for the Factual Group which is amusing in a way because as an independent now I have struggled - in fact, so far failed - to get anything commis- sioned by the BBC. One remains hopeful and keeps trying,” he smiles thinly.

“I just found it to be the worst- run organisation. I used to tell that to John Birt who after all had been my boss at LWT. He’d laugh politely and wouldn’t comment. The BBC has never really come to terms with the existence of the independent sector and has never really found a way, in my view, of dealing on a basis of parity and fairness with indies.

“Having executives like me was their attempt at the time to try and deal with it and, in some ways having a direct point of entry worked quite successfully; in fact, so successfully that they sub- sequently changed the system. Now it’s incredibly complicated to get programmes commissioned.

“I’m making a programme about El Greco at the moment. He used to be commissioned by individuals to make paintings and that was often problematic enough. Imagine if there was a committee of 25 different peo- ple? He’d never have painted anything, and he certainly would never have worked for the BBC!”

“It’s strange, because they’ve made so many positive strides in other areas. For example, they’ve been incredibly brave in taking on the government. As it hap- pens, they’ve also been extreme- ly supportive of BAFTA and worked closely with us over a number of years to mutual bene- fit. If only it was always so good.”

As far as he’s concerned the cavalry “mercifully” arrived in the form of the newly-launched Channel Five who poached him in 1996 to become Controller of Features and Arts.

Could he then be accused of helping create one of Dawn Airey’s famous three Fs? “It was- n’t football and it wasn’t films,” he explains helpfully, adding that, in fact, he had “a wide- ranging brief” which resulted in his commissioning a substantial proportion of the channel’s top twenty performing shows. Notably, he says, “the first of the modern genre of property pro- grammes” which, in the wake of C5’s Hot Property and House

12

Photo by Richard Kendal