Page 111 - Kosovo Metohija Heritage

P. 111

lioned window on the upper level emerges through the body of the exonarthex to rise, with its free upper sec- tion, high above the church’s dome. Open on all sides so that the entire town could hear the church-bells, its light- -weight construction and transparency as well as sturdy proportions embrace the ceremonial western side of the complex. Today, however, like so many other monumen- tal façades it is obscured by a network of narrow streets of the thickly populated quarter “on the Ljeviša,” as this part of the town was known in the Middle ages.

The variety of the construction elements used in re- building the Prizren cathedral can readily be noted in its interior arches adequately following the nature of the avail- able space. But the real wealth of forms and architectural texture is most obvious in the façades, till then unknown to Serbian architecture. in keeping with Byzantine build- ing methods, the façade was made of blocks of warm-toned tufa with bricks of different shapes and shades and broad sculptural clasps, altogether creating rich surfaces and warm color blends. The façade itself is highly diverse with its apertures, lunettes and archivolts, shallow pillasters and niches. Some of them, especially elements of the arch- es, were made exclusively of bricks in multiform sequenc- es and free motifs without regular repetitions, ranging from decoratively disposed elements to a series of deli- cate ornaments formed for instance, by the stylized pat- terns of wavesets or incised cross-like small vessels.

This manner of elaborating the Ljeviša façade was a novelty for the Serbs and meant that the earlier, simple broad wall surfaces had been abandoned, but more than

that, it was the most representative expression of a long and carefully nurtured practice which had produced ma- jor works throughout Byzantium. as was often the case in both earlier and more recent history, examples similar to these Serbian structures in Serbia are preserved in Thes- salonica. Still, immediate influences on the skillful build- ers who restored the Church of the Mother of God in Prizren would to all appearances have to be sought in the workshops of epirus. From there, particularly in the 13th century, builders fanned out over a broad area; their tech- niques could be recognized in places which, after the Ser- bian penetration into the northern regions of Byzantium, lay within its borders.

Two inscriptions on the external side of the altar apse are testimony to the building of the church and those peo- ple associated with it. Done in a rare form of full, clear lettering as was the custom of the time, the inscriptions were pressed into soft clay, which was fired and built into the wall as an ornamental band. The higher, shorter in- scription mentions Prizren Bishop Sava whose share in the restoration work is recalled by other bricks (five of which have survived) and which simply note the bishop’s name without hierarchical titles. The lower, longer text cites, in a first-person statement by the founder of the church, King Milutin himself, that he “maintained the Church of the Mother of God of Ljeviša” from the very moment of its foundation. at the end of the inscription stands the year 1306–7, probably indicating the date of the building of the eastern section rather than the com- pletion of the entire church.

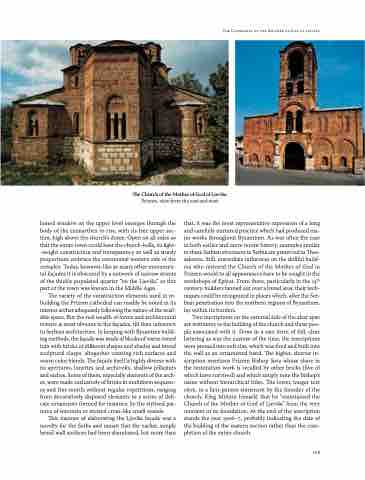

The Church of the Mother of God of Ljeviša, Prizren, view from the east and west

The Cathedral of the Mother of God of Ljeviša

109