Page 64 - CAO 25th Ann Coffee Table Book

P. 64

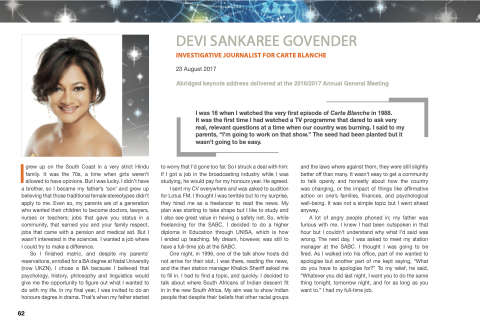

DEVI SANKAREE GOVENDER

INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALIST FOR CARTE BLANCHE

23 August 2017

Abridged keynote address delivered at the 2016/2017 Annual General Meeting

I was 16 when I watched the very first episode of Carte Blanche in 1988.

It was the first time I had watched a TV programme that dared to ask very real, relevant questions at a time when our country was burning. I said to my parents, “I’m going to work on that show.” The seed had been planted but it wasn’t going to be easy.

Igrew up on the South Coast in a very strict Hindu family. It was the 70s, a time when girls weren’t allowed to have opinions. But I was lucky. I didn’t have

a brother, so I became my father’s ‘son’ and grew up believing that those traditional female stereotypes didn’t apply to me. Even so, my parents are of a generation who wanted their children to become doctors, lawyers, nurses or teachers; jobs that gave you status in a community, that earned you and your family respect, jobs that came with a pension and medical aid. But I wasn’t interested in the sciences. I wanted a job where I could try to make a difference.

So I finished matric, and despite my parents’ reservations, enrolled for a BA degree at Natal University (now UKZN). I chose a BA because I believed that psychology, history, philosophy and linguistics would give me the opportunity to figure out what I wanted to do with my life. In my final year, I was invited to do an honours degree in drama. That’s when my father started

to worry that I’d gone too far. So I struck a deal with him: If I got a job in the broadcasting industry while I was studying, he would pay for my honours year. He agreed.

I sent my CV everywhere and was asked to audition for Lotus FM. I thought I was terrible but to my surprise, they hired me as a freelancer to read the news. My plan was starting to take shape but I like to study and I also see great value in having a safety net. So, while freelancing for the SABC, I decided to do a higher diploma in Education through UNISA, which is how I ended up teaching. My dream, however, was still to have a full-time job at the SABC.

One night, in 1996, one of the talk show hosts did not arrive for their slot. I was there, reading the news, and the then station manager Khalick Sheriff asked me to fill in. I had to find a topic, and quickly. I decided to talk about where South Africans of Indian descent fit in in the new South Africa. My aim was to show Indian people that despite their beliefs that other racial groups

and the laws where against them, they were still slightly better off than many. It wasn’t easy to get a community to talk openly and honestly about how the country was changing, or the impact of things like affirmative action on one’s families, finances, and psychological well-being. It was not a simple topic but I went ahead anyway.

A lot of angry people phoned in; my father was furious with me. I knew I had been outspoken in that hour but I couldn’t understand why what I’d said was wrong. The next day, I was asked to meet my station manager at the SABC. I thought I was going to be fired. As I walked into his office, part of me wanted to apologise but another part of me kept saying, “What do you have to apologise for?” To my relief, he said, “Whatever you did last night, I want you to do the same thing tonight, tomorrow night, and for as long as you want to.” I had my full-time job.

62