Page 26 - QARANC Vol 18 No 2 2020

P. 26

24 The Gazette QARANC Association

Covid-19 – Working as a Nurse in an NHS Hospital

In March 2017, I achieved the goal I had been working towards for the previous three years when I became a qualified nurse and was given a position on an emergency surgical ward at the Countess of Chester Hospital. I joined 208 (Liverpool) Field Hospital as a first year student nurse. Having gained experience in the surgical field I was informed that the ward I was working on was to become the winter escalation ward. This required me to adapt to an entirely different approach to nursing and to expand my knowledge of respiratory conditions and chronic medical conditions.

However, it came as a blessing in disguise for what was to come next. In January 2020, Coronavirus/Covid-19 was becoming the subject at the forefront of all our minds. The questions being asked ... Would the virus spread to the UK and the rest of Europe? Was it already here without our knowledge? What were the symptoms and how many people would it potentially kill? We knew the storm was coming and that we needed to be strong and work together as a team to prevent and protect people from this virus. As a generation that had experienced the outbreaks of fatal viruses such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2002 and the Ebola virus epidemic of 2014, no one could really have been prepared for Coronavirus.

I had never met anyone that had been affected by any of these viruses and I fully expected this to be the same; I expected that it would be something that we would see on the news or something that I may be able to help with, as had several of fellow unit members before me, but never expected it to be something that would flood our hospital and require the construction of an emergency Nightingale hospital to manage.

I never expected to witness or care for someone that would die from the virus or have any family members, friends of colleagues suffer the effects of it. I was shopping with a friend and fellow unit member in Manchester when the news came across the radio that Covid-19 had been classified as a pandemic. In that moment it all started to feel very real and we knew that everything was about to change.

In mid-March, I began a run of night shifts. I was walking down the corridor to my ward and had to now pass through three newly installed isolation doors and sanitation stations and noted that offices had been transformed into donning and doffing rooms. As soon as I entered the ward, I walked past a side room with a closed door and a droplet precautions warning sign attached to the door. I went to the nursing station for a safety brief where the nurse in charge gave me a briefing on when entering this room you now had to wear level 2 personal protective equipment (PPE). This was both my first experience of wearing it and was the first suspected Covid-19 patient that I would care for. I had already been fitted for my FFP3 mask and I had to quickly adapt to donning this equipment on entering the patient’s room. Over the mask we wore a full-face visor, a full-length gown and gloves thicker and longer than the ones we were accustomed to.

On March 23 the lockdown of the UK was announced; we were only allowed to go to work if we were in a key role, unessential travel was banned. The number of patients admitted with confirmed Covid-19 sadly sky rocketed. The ward I worked on was situated near the specialist respiratory unit and we were informed that both units may need to join together. We were now educated in non-invasive ventilation and the difference between CPap (continuous positive airway pressure) and BiPap (bilevel positive airway pressure).

The word ‘Coronavirus’ flooded our television screens and the columns of our newspapers. It was impossible not to hear about it or see it daily, particularly in hospital. Sadly, Coronavirus took its grip on the hospital; I quickly lost count of the number of patients I lost on a duty shift. There was little we could do as many patients were under a do not attempt cardiac pulmonary resuscitation order.

Nurses are trained to try and keep our emotions hidden in front of patients and colleagues, but also to try and find ways to not take stress home; this is meant to benefit our mental health, however, shift after shift, losing patient after patient, eventually took its toll and I had several emotional moments which

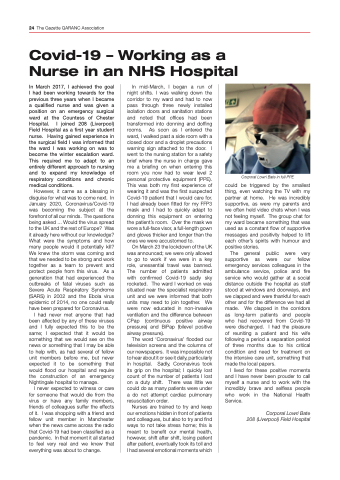

Corporal Lowri Bate in full PPE

could be triggered by the smallest thing, even watching the TV with my partner at home. He was incredibly supportive, as were my parents and we often held video chats when I was not feeling myself. The group chat for my ward became something that was used as a constant flow of supportive messages and positivity helped to lift each other’s spirits with humour and positive stories.

The general public were very supportive as were our fellow emergency services colleagues in the ambulance service, police and fire service who would gather at a social distance outside the hospital as staff stood at windows and doorways, and we clapped and were thankful for each other and for the difference we had all made. We clapped in the corridors as long-term patients and people who had recovered from Covid-19 were discharged. I had the pleasure of reuniting a patient and his wife following a period a separation period of three months due to his critical condition and need for treatment on the intensive care unit, something that made the local papers.

I lived for these positive moments and I have never been prouder to call myself a nurse and to work with the incredibly brave and selfless people who work in the National Health Service.

Corporal Lowri Bate 208 (Liverpool) Field Hospital