Page 299 - Western Civilization A Brief History, Volume I To 1715 9th - Jackson J. Spielvogel

P. 299

beyond approving measures pro-

posed by the Lords, during Edward’s North reign the Commons did begin the Sea practice of drawing up petitions, EN

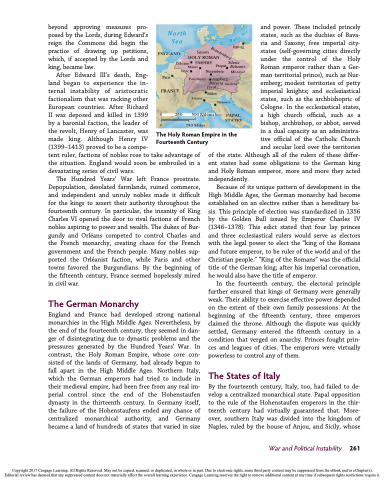

and power. These included princely states, such as the duchies of Bava- ria and Saxony; free imperial city- states (self-governing cities directly under the control of the Holy Roman emperor rather than a Ger- man territorial prince), such as Nur- emberg; modest territories of petty imperial knights; and ecclesiastical states, such as the archbishopric of Cologne. In the ecclesiastical states, a high church official, such as a bishop, archbishop, or abbot, served in a dual capacity as an administra- tive official of the Catholic Church and secular lord over the territories

of the state. Although all of the rulers of these differ- ent states had some obligations to the German king and Holy Roman emperor, more and more they acted independently.

Because of its unique pattern of development in the High Middle Ages, the German monarchy had become established on an elective rather than a hereditary ba- sis. This principle of election was standardized in 1356 by the Golden Bull issued by Emperor Charles IV (1346–1378). This edict stated that four lay princes and three ecclesiastical rulers would serve as electors with the legal power to elect the “king of the Romans and future emperor, to be ruler of the world and of the Christian people.” “King of the Romans” was the official title of the German king; after his imperial coronation, he would also have the title of emperor.

In the fourteenth century, the electoral principle further ensured that kings of Germany were generally weak. Their ability to exercise effective power depended on the extent of their own family possessions. At the beginning of the fifteenth century, three emperors claimed the throne. Although the dispute was quickly settled, Germany entered the fifteenth century in a condition that verged on anarchy. Princes fought prin- ces and leagues of cities. The emperors were virtually powerless to control any of them.

The States of Italy

By the fourteenth century, Italy, too, had failed to de- velop a centralized monarchical state. Papal opposition to the rule of the Hohenstaufen emperors in the thir- teenth century had virtually guaranteed that. More- over, southern Italy was divided into the kingdom of Naples, ruled by the house of Anjou, and Sicily, whose

War and Political Instability 261

D

Cologne EMPIRE Prague Silesia

Bohemia

a

a

a

an

n

n

n

nzig

LAND which, if accepted by the Lords and H

N

Saxony

HOLY ROMAN

NG

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

GL

L

king, became law.

After Edward Ill’s death, Eng-

C

Main ier

z

n

z

T

Palat

T

T

T

T

T

r

r

r

i

i

i

Nuremberg

Morav

v

v

vi

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

a

a

a

Paris FRANCE

inate

t

i

Augsbu Bavaria Austria

land began to experience the in-

ternal instability of aristocratic

factionalism that was racking other

European countries. After Richard

II was deposed and killed in 1399

by a baronial faction, the leader of

the revolt, Henry of Lancaster, was

made king. Although Henry IV

(1399–1413) proved to be a compe-

tent ruler, factions of nobles rose to take advantage of the situation. England would soon be embroiled in a devastating series of civil wars.

The Hundred Years’ War left France prostrate. Depopulation, desolated farmlands, ruined commerce, and independent and unruly nobles made it difficult for the kings to assert their authority throughout the fourteenth century. In particular, the insanity of King Charles VI opened the door to rival factions of French nobles aspiring to power and wealth. The dukes of Bur- gundyandOrleanscompetedtocontrolCharlesand the French monarchy, creating chaos for the French government and the French people. Many nobles sup- ported the Orleanist faction, while Paris and other towns favored the Burgundians. By the beginning of the fifteenth century, France seemed hopelessly mired in civil war.

The German Monarchy

England and France had developed strong national monarchies in the High Middle Ages. Nevertheless, by the end of the fourteenth century, they seemed in dan- ger of disintegrating due to dynastic problems and the pressures generated by the Hundred Years’ War. In contrast, the Holy Roman Empire, whose core con- sisted of the lands of Germany, had already begun to fall apart in the High Middle Ages. Northern Italy, which the German emperors had tried to include in their medieval empire, had been free from any real im- perial control since the end of the Hohenstaufen dynasty in the thirteenth century. In Germany itself, the failure of the Hohenstaufens ended any chance of centralized monarchical authority, and Germany became a land of hundreds of states that varied in size

g

u

r

r

g

a

Tyrol

a

Gen

a

n

Milan Flo

o

o

a

o

o

orence

0 Kilomete

S

Miles

The Holy Roman Empire in the

e

ers

L TATES

0 2

2 0

5

50 250

5

5

5

50

P AP

L

T

T

T

P

P

P

P

P

P

P

P

P

P

P

P

P

P

P

P

P

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

L

L

S

S

S

S

Fourteenth Century

Copyright 2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

a

e

S

c

i

t

l

a

B

Brandenburg