Page 10 - Early Naturalists of the Black Range

P. 10

Some caution should be exercised in this area. Some of the more “popular” new works may be somewhat suspect, and if you would like to apply the native knowledges referenced, you may wish to verify that information from multiple sources.

Early Spanish Explorations

The early Spanish explorers had a utilitarian approach to natural history. The search for riches and their attempts to spread their religion were the major motivations for their travels. A good part of natural history is about figuring out the geography, however, and they had a lot of that to accomplish.

Álvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca

1535: Cabeza de Vaca was part of the ill-fated Panfilo de Narváez expedition to Florida. After many adventures (most of which no one would want to have) he ended up in Mexico. Perhaps, he crossed the Black Range on that journey, probably in 1535 or 1536. He described pinyon and another pine growing in the region. (Cabeza de Vaca's adventures in the unknown interior of America, Cyclone Covey, translator and editor, 1983, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, N.M.)

It is possible that Cabeza de Vaca heard about the copper mines at Santa Rita. Buckingham Smith’s translation of the description of the trip (The Narrative of Álvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca; Translated by Buckingham Smith, 1851) includes this bit of insight: “Among the articles that were given to us, Andrés Dorantes received a bell of copper, thick and large, figured with a face, which they had shown, greatly

prizing it. They told him that they had gotten it from others, their neighbors; and we asking them whence these had obtained it, they said that it had been brought from the direction of the north, where there was much copper, and that it was highly esteemed. We concluded that whencesoever it came there was a foundery (sic), and that work was done in hollow form.” (p. 92)

The original description of the journey was published in 1542 as "La relacion que dio Aluar Nuñez Cabeça de Vaca de lo acaescido en las Indias en la armada donde yua por Gouernador Páphilo de Narbáez desde el año de veynte y siete hasta el año de treynta y seys ..." Smith’s translation was from the second edition, which was published in 1555.

Francisco Vásquez de Coronado

1540-1542. The account of Coronado’s travels was written by Pedro Reyes Castañeda. There have been various translations and interpretations of his

work. “The term ‘pino’ was used by the chronicler of the expedition when describing the trees observed. Reference was made to ‘pillars of pine’, which may have been ponderosa pine, that were used by the Pueblo Indians to construct footbridges. Extensive montane pine forests in the region were mentioned by Coronado, as they were by several subsequent Spanish explorers in the late 1500s.” (Clevy Lloyd Strout, 1971. “Flora and fauna mentioned in the journals of the Coronado Expedition”, Great Plains Journal ll (1): 5-40.)

Diego Gutierrez

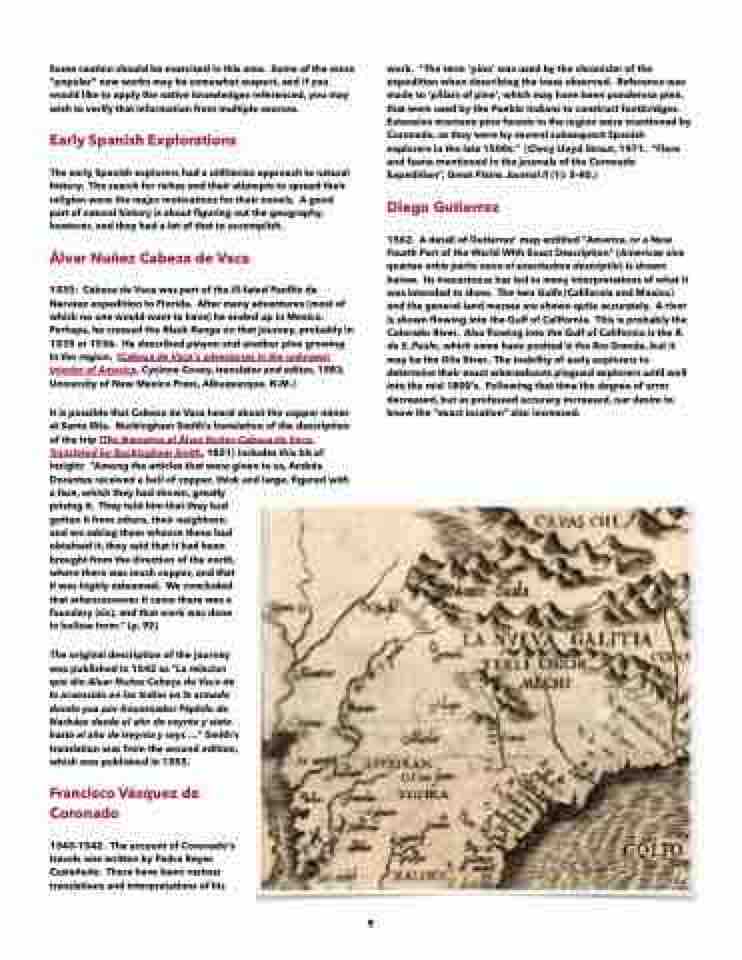

1562. A detail of Gutierrez’ map entitled “America, or a New Fourth Part of the World With Exact Description” (Americae sive quartae orbis partis nova et exactissima descriptio) is shown below. Its inexactness has led to many interpretations of what it was intended to show. The two Gulfs (California and Mexico) and the general land masses are shown quite accurately. A river is shown flowing into the Gulf of California. This is probably the Colorado River. Also flowing into the Gulf of California is the R. de S. Paulo, which some have posited is the Rio Grande, but it may be the Gila River. The inability of early explorers to determine their exact whereabouts plagued explorers until well into the mid 1800’s. Following that time the degree of error decreased, but as professed accuracy increased, our desire to know the “exact location” also increased.

9