Page 18 - 07_Bafta ACADEMY_Stephen Fry_ok

P. 18

Focus on Interactive

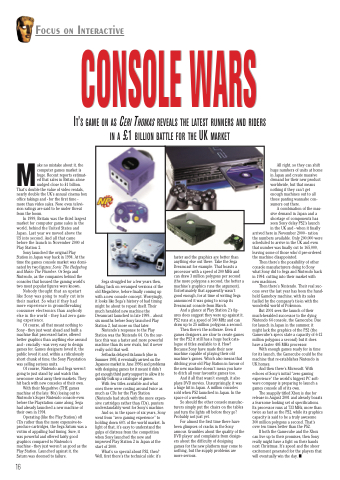

CONSOLEWARS

CONSOLEWARS

IT’S GAME ON AS CERI THOMAS REVEALS THE LATEST RUNNERS AND RIDERS IN A £1 BILLION BATTLE FOR THE UK MARKET

Make no mistake about it, the computer games market is huge. Recent reports estimat- ed that sales in Britain alone nudged close to £1 billion. That’s double the value of video rentals, nearly double the UK’s annual cinema box office takings and - for the first time - more than video sales. Now, even televi- sion ratings are said to be under threat from the boom.

In 1999, Britain was the third largest market for computer game sales in the world, behind the United States and Japan. Last year we moved above the US into second. And all that came before the launch in November 2000 of Play Station 2.

Sony launched the original Play Station in Japan way back in 1994. At the time the games console market was domi- nated by two figures: Sonic The Hedgehog and Mario The Plumber. Or Sega and Nintendo, as the companies behind the consoles that housed the gaming world’s two most popular figures were known.

Nobody thought that an upstart like Sony was going to really cut into their market. So what if they had more experience in groundbreaking consumer electronics than anybody else in the world - they had zero gam- ing experience.

Of course, all that meant nothing to Sony - they just went ahead and built a machine that processed faster, offered better graphics than anything else around and - crucially - was very easy to design games for. Games designers loved it, the public loved it and, within a ridiculously short chunk of time, the Sony Playstation was selling serious units.

Of course, Nintendo and Sega weren’t going to just stand by and watch this newcomer steal away their markets. They hit back with new consoles of their own.

With their Megadrive (THE games machine of the late ‘80s) losing out to Nintendo’s Super Nintendo console even before the Playstation came along, Sega had already launched a new machine of their own in 1994.

Operating (like the Play Station) off CDs rather than the more expensive-to- produce cartridges, the Sega Saturn was a victim of appalling bad timing. Sure, it was powerful and offered fairly good graphics compared to Nintendo’s machine - they just weren’t as good as the Play Station. Launched against it, the Saturn was doomed to failure.

16

Sega struggled for a few years then, falling back on revamped versions of the old Megadrive, before finally coming up with a new console concept. Worryingly, it looks like Sega’s history of bad timing might be about to repeat itself. Their much heralded new machine the Dreamcast launched in late 1999... about six months before Sony launched Play Station 2, but more on that later.

Nintendo’s response to the Play Station was the Nintendo 64. On the sur- face this was a faster and more powerful machine than its new rivals, but it never really sold that well.

Setbacks delayed its launch (due in Summer 1995, it eventually arrived on the Japanese market in June 1996) and problems with designing games for it meant it didn’t get enough third party support to allow it to quickly bulk up a catalogue of games.

With few titles available and what ones there were costing around twice as much as CDs for the Play Station (Nintendo had stuck with the more expen- sive cartridges rather than CDs), punters understandably went for Sony’s machine.

And so, in the space of six years, Sony went from “zero gaming experience” to holding down 60% of the world market. In light of that, it’s easy to understand the gulps of distress from the competition when Sony launched the new and improved Play Station 2 in Japan at the start of 2000.

What’s so special about PS2, then? Well, first there’s the technical side: it’s

faster and the graphics are better than anything else out there. Take the Sega Dreamcast for example. That boasts a processor with a speed of 200 MHz and can draw 3 million polygons per second (the more polygons a second, the better a machine’s graphics runs the argument). Unfortunately that apparently wasn’t good enough, for at time of writing Sega announced it was going to scrap its Dreamcast console from March.

And a glance at Play Station 2’s fig- ures does suggest they were up against it. PS2 runs at a speed of 300 MHz and can draw up to 25 million polygons a second.

Then there’s the software. Even if games designers are slow to create games for the PS2 it still has a huge back cata- logue of titles available to it. How? Because Sony have made their new machine capable of playing their old machine’s games. Which also means that ditching your old Play Station in favour of the new machine doesn’t mean you have to ditch all your favourite games too.

And if all that wasn’t enough, it also plays DVD movies. Unsurprisingly, it was a huge hit in Japan. A million consoles sold when PS2 launched in Japan. In the space of a weekend.

So should the other console manufac- turers simply put the chairs on the tables and turn the lights off before they go? Probably not just yet.

For almost the first time there have been glimpses of cracks in the Sony armour. Grumbles about the quality of the DVD player and complaints from design- ers about the difficulty of designing games for the new platform may come to nothing, but the supply problems are more serious.

All right, so they can shift huge numbers of units at home in Japan and create massive demand for their new product worldwide, but that means nothing if they can’t get enough machines out to all those panting wannabe con- sumers out there.

A combination of the mas- sive demand in Japan and a shortage of components has seen Sony delay PS2’s launch in the UK and - when it finally

arrived here in November 2000 - ration the numbers available. Only 200,000 were scheduled to arrive in the UK and even that number was finally cut to 165,000, leaving some of those who’d pre-ordered the machine disappointed.

Then there’s the possibility of other console manufacturers doing to Sony what Sony did to Sega and Nintendo back in 1994: cutting into their market with new machines.

Then there’s Nintendo. Their real suc- cess over the last year has been the hand- held Gameboy machine, with its sales fuelled by the company’s tie-in with the wonderful world of Pokemon.

But 2001 sees the launch of their much-heralded successor to the dying Nintendo 64 console, the Gamecube. Due for launch in Japan in the summer, it might lack the graphics of the PS2 (the Gamecube’s specs state a capacity of 6-12 million polygons a second) but it does have a faster 405 MHz processor.

With enough games ready for in time for its launch, the Gamecube could be the machine that re-establishes Nintendo in UK homes.

And then there’s Microsoft. With echoes of Sony’s initial “zero gaming experience” the world’s biggest PC soft- ware company is preparing to launch a games console all of its own.

The snappily titled Xbox is due for release in August 2001 and already boasts a fearsome looking set of specifications. Its processor runs at 733 MHz, more than twice as fast as the PS2, while its graphics capacity is said to be a truly awesome 300 million polygons a second. That’s over ten times better than the PS2.

If both the Gamecube and the Xbox can live up to their promises, then Sony really might have a fight on their hands next Christmas. It’s speed and the sheer excitement generated for the players that will eventually win the day. ■