Page 11 - 05_Bafta ACADEMY_Phil Jupitus_ok

P. 11

F BRITISH

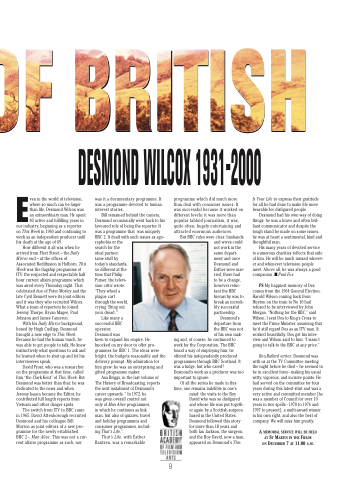

DESMOND WI LCOX 1931-2000

Even in the world of television, where so much can be larger than life, Desmond Wilcox was an extraordinary man. He spent 40 active and fulfilling years in our industry, beginning as a reporter onThisWeekin1960andcontinuingto work as an independent producer until his death at the age of 69.

How different it all was when he arrived from Fleet Street – the Daily Mirror end – at the offices of Associated Rediffusion in Holborn. This Week was the flagship programme of ITV, the respected and respectable half hour current affairs programme which was aired every Thursday night. That celebrated duo of Peter Morley and the late Cyril Bennett were its joint editors and it was they who recruited Wilcox. What a team of reporters he joined: Jeremy Thorpe, Bryan Magee, Paul Johnson and James Cameron.

With his Daily Mirror background, honed by Hugh Cudlipp, Desmond brought a new edge to This Week. Because he had the human touch, he was able to get people to talk. He knew instinctively what questions to ask and he learned when to shut up and let his interviewees speak.

David Frost, who was a researcher on the programme at that time, called him “the Clark Kent” of This Week. But Desmond was better than that: he was dedicated to the news and when Jeremy Isaacs became the Editor, he contributed full length reports from Vietnam and other danger spots.

The switch from ITV to BBC came in 1965. David Attenborough recruited Desmond and his colleague Bill Morton as joint editors of a new pro- gramme for the newly established BBC2- ManAlive.Thiswasnotacur- rent affairs programme as such, nor

was it a documentary programme. It was a programme devoted to human interest stories.

Bill remained behind the camera, Desmond occasionally went back to his favoured role of being the reporter. It wasaprogrammethat wasuniquely BBC 2. It dealt with such issues as ago- raphobia or the

search for the

ideal partner:

tame stuff by

today’s standards,

so different at the

time that Philip

Purser, the televi-

sion critic wrote:

“They wheel a

plague cart

through the world,

crying ‘Bring out

your dread.’”

Like many a

successful BBC

operator,

Desmond was

keen to expand his empire. He knocked on my door to offer pro- grammes for BBC 1. The ideas were bright, the budgets reasonable and the delivery prompt. My admiration for him grew: he was an enterprising and gifted programme maker.

Asa Briggs, in the last volume of The History of Broadcasting, reports the next instalment of Desmond’s career upwards. “ In 1972, he

was given overall control not

only of Man Alive programmes,

in which he continues as link

man, but also of quizzes, travel

and holiday programmes and consumer programmes, includ-

ing That’s Life.”

That’s Life, with Esther Rantzen, was a remarkable

programme which did much more than deal with consumer issues. It was successful because it worked on different levels: it was more than popular tabloid journalism, it was, quite often, hugely entertaining and attractedenormousaudiences.

But BBC rules were clear: husbands and wives could

not work in the same depart- ment and once Desmond and Esther were mar- ried, there had to be a change, however reluc- tant the BBC hierarchy was to break an incredi- bly successful partnership.

Desmond’s departure from the BBC was not of his own mak-

ing and, of course, he continued to work for the Corporation. The BBC found a way of employing him; he offered his independently produced programmes through BBC Scotland. It was a fudge, but who cared? Desmond’s work as a producer was too important to ignore.

Of all the series he made in this time, one remains indelible in one’s mind: the visits to the Boy

David who was so disfigured and whose life was put togeth- er again by a Scottish surgeon based in the United States. Desmond followed this story for more than 18 years and both Ian Jackson, the surgeon, and the Boy David, now a man, appeared on Desmond’s This

Is Your Life to express their gratitude for all he had done to make life more bearable for disfigured people.

Desmond had his own way of doing things: he was a brave and often bril- liant communicator and despite the toughstandhemadeonsomeissues, he was at heart a sentimental, kind and thoughtful man.

His many years of devoted service to numerous charities reflects that side of him. He will be much missed wherev- er and whenever television people meet. Above all, he was always a good companion. ■ Paul Fox

PS My happiest memory of Des comes from the 1964 General Election. Harold Wilson coming back from Huyton on the train to No 10 had refused to be interviewed by John Morgan. “Nothing for the BBC,” said Wilson. I sent Des to King’s Cross to meet the Prime Minister, assuming that he’d still regard Des as an ITV man. It worked beautifully. Des got his inter- view and Wilson said to him: “I wasn’t going to talk to the BBC at any price.”

Bea Ballard writes: Desmond was with us at the TV Committee meeting the night before he died – he seemed to be in excellent form - making his usual witty, vigorous, and incisive points. He had served on the committee for four years during this latest stint and was a very active and committed member [he was a member of Council for over 10 years in two spells - 1970 to 1976 and 1997 to present], a multi-award winner in his own right, and also the best of company. We will miss him greatly.

A MEMORIAL SERVICE WILL BE HELD AT ST MARTIN IN THE FIELDS ON DECEMBER 7 AT 11:00 A.M.

9

O