Page 100 - JM Book 9/2020

P. 100

as he shook Jefferson’s hand. “Your words have helped to make our dream a reality. Thank you dear friend.” He continued to shake Jefferson’s hand.

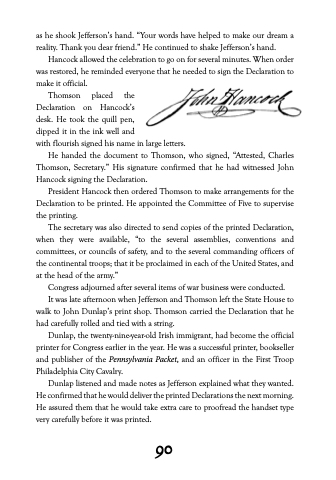

Hancock allowed the celebration to go on for several minutes. When order was restored, he reminded everyone that he needed to sign the Declaration to make it official.

Thomson placed the

Declaration on Hancock’s

desk. He took the quill pen,

dipped it in the ink well and

with flourish signed his name in large letters.

He handed the document to Thomson, who signed, “Attested, Charles Thomson, Secretary.” His signature confirmed that he had witnessed John Hancock signing the Declaration.

President Hancock then ordered Thomson to make arrangements for the Declaration to be printed. He appointed the Committee of Five to supervise the printing.

The secretary was also directed to send copies of the printed Declaration, when they were available, “to the several assemblies, conventions and committees, or councils of safety, and to the several commanding officers of the continental troops; that it be proclaimed in each of the United States, and at the head of the army.”

Congress adjourned after several items of war business were conducted.

It was late afternoon when Jefferson and Thomson left the State House to walk to John Dunlap’s print shop. Thomson carried the Declaration that he had carefully rolled and tied with a string.

Dunlap, the twenty-nine-year-old Irish immigrant, had become the official printer for Congress earlier in the year. He was a successful printer, bookseller and publisher of the Pennsylvania Packet, and an officer in the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry.

Dunlap listened and made notes as Jefferson explained what they wanted. He confirmed that he would deliver the printed Declarations the next morning. He assured them that he would take extra care to proofread the handset type very carefully before it was printed.

90