Page 173 - Kosovo Metohija Heritage

P. 173

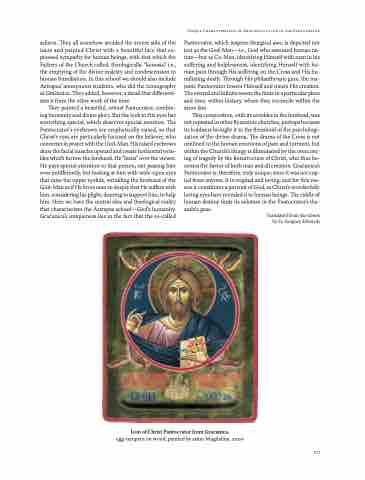

selinos. They all somehow avoided the severe side of the issue and painted Christ with a beautiful face that ex- pressed sympathy for human beings, with that which the Fathers of the Church called, theologically, “kenosis,” i.e., the emptying of the divine majesty and condescension to human humiliation. in this school we should also include astrapas’ anonymous students, who did the iconography at Gračanica. They added, however, a detail that differenti- ates it from the other work of the time.

They painted a beautiful, robust Pantocrator, combin- ing humanity and divine glory. But the look in His eyes has something special, which deserves special mention. The Pantocrator’s eyebrows are emphatically raised, so that Christ’s eyes are particularly focused on the believer, who converses in prayer with the God-Man. His raised eyebrows draw the facial muscles upward and create horizontal wrin- kles which furrow the forehead. He “leans” over the viewer. He pays special attention to that person, not passing him over indifferently, but looking at him with wide-open eyes that raise the upper eyelids, wrinkling the forehead of the God-Man as if He loves man so deeply that He suffers with him, considering his plight, desiring to support him, to help him. Here we have the central idea and theological reality that characterizes the astrapas school—God’s humanity. Gračanica’s uniqueness lies in the fact that the so-called

Unique Characteristics of Gračanica’s icon of the Pantocrator

Pantocrator, which inspires liturgical awe, is depicted not just as the God-Man—i.e., God who assumed human na- ture—but as Co-Man, identifying Himself with man in his suffering and helplessness, identifying Himself with hu- man pain through His suffering on the Cross and His hu- miliating death. Through His philanthropic gaze, the ma- jestic Pantocrator lowers Himself and meets His creation. The eternal and infinite meets the finite in a particular place and time, within history, where they reconcile within the same fate.

This composition, with its wrinkles in the forehead, was not repeated in other Byzantine churches, perhaps because its boldness brought it to the threshold of the psychologi- zation of the divine drama. The drama of the Cross is not confined to the human emotions of pain and torment, but within the Church’s liturgy is illuminated by the overcom- ing of tragedy by the Resurrection of Christ, who thus be- comes the Savior of both man and all creation. Gračanica’s Pantocrator is, therefore, truly unique, since it was not cop- ied from anyone. it is original and loving, and for this rea- son it constitutes a portrait of God, as Christ’s wonderfully loving eyes have revealed it to human beings. The riddle of human destiny finds its solution in the Pantocrator’s the- andric gaze.

Translated from the Greek by Fr. Gregory edwards

Icon of Christ Pantocrator from Gračanica, egg-tempera on wood, painted by sister Magdalina, 2000

171