Page 62 - Constructing Craft

P. 62

Rangimarie Hetet, (Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Kinohaku) and her daughter Diggeress

Rangitutahi Te Kanawa, (Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Kinohaku), made a major

contribution to ensuring that tradition was acknowledged, if not directly applied,

when interest in forms of Māori art and craft increased after the war. Rangimarie

Hetet was born in 1892 and was taught weaving by her extended family, but it was

not until 1951, when she became a founding member of the Māori Women’s

Welfare League, that she began to share her skills with the community and children

in schools. While Rangimarie would not take part in ‘innovations’ such as using

49

man-made fibres instead of traditional plant fibres, Diggeress was prepared to

adapt. When asked how she would deal with the diminishing supply of natural

dyestuffs she responded: ‘I guess we’ll do what our old people would have done, …

50

experiment with other plants to see what alternatives we might find.’ It

demonstrated a blending of tradition with the innovative approach that became an

important and contested aspect of the studio craft movement.

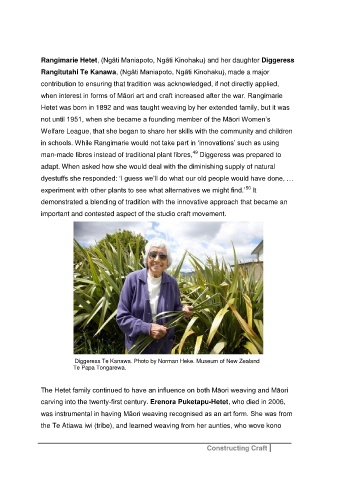

Diggeress Te Kanawa. Photo by Norman Heke. Museum of New Zealand

Te Papa Tongarewa.

The Hetet family continued to have an influence on both Māori weaving and Māori

carving into the twenty-first century. Erenora Puketapu-Hetet, who died in 2006,

was instrumental in having Māori weaving recognised as an art form. She was from

the Te Atiawa iwi (tribe), and learned weaving from her aunties, who wove kono

Constructing Craft