Page 161 - GV2020 Portfolio Master

P. 161

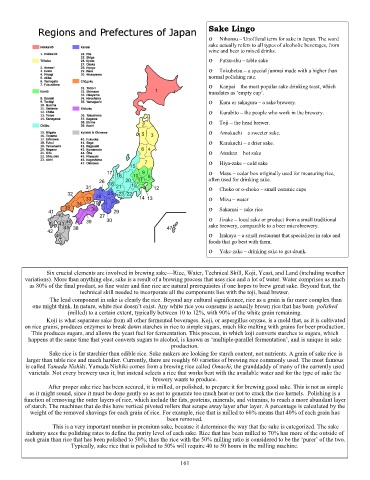

Sake Lingo

Nihonsu – Unofficial term for sake in Japan. The word

sake actually refers to all types of alcoholic beverages, from

wine and beer to mixed drinks.

Futsu-shu – table sake

Tokubetsu – a special junmai made with a higher than

normal polishing rate.

Kanpai – the most popular sake drinking toast, which

translates as ‘empty cup’.

Kura or sakagura – a sake brewery.

Kurabito – the people who work in the brewery.

Toji – the head brewer.

Amakuchi – a sweeter sake.

Karakuchi – a drier sake.

Atsukan – hot sake

Hiya-zake – cold sake

Masu – cedar box originally used for measuring rice,

often used for drinking sake.

Choko or o-choko – small ceramic cups

Mizu – water

Sakamai – sake rice

Jizake – local sake or product from a small traditional

sake brewery, comparable to a beer microbrewery.

Izakaya – a small restaurant that specializes in sake and

foods that go best with them.

Yake-zake – drinking sake to get drunk.

Six crucial elements are involved in brewing sake—Rice, Water, Technical Skill, Koji, Yeast, and Land (including weather

variations). More than anything else, sake is a result of a brewing process that uses rice and a lot of water. Water comprises as much

as 80% of the final product, so fine water and fine rice are natural prerequisites if one hopes to brew great sake. Beyond that, the

technical skill needed to incorporate all the components lies with the toji, head brewer.

The lead component in sake is clearly the rice. Beyond any cultural significance, rice as a grain is far more complex than

one might think. In nature, white rice doesn’t exist. Any white rice you consume is actually brown rice that has been polished

(milled) to a certain extent, typically between 10 to 12%, with 90% of the white grain remaining.

Koji is what separates sake from all other fermented beverages. Koji, or aspergillus oryzae, is a mold that, as it is cultivated

on rice grains, produces enzymes to break down starches in rice to simple sugars, much like malting with grains for beer production.

This produces sugars, and allows the yeast fuel for fermentation. This process, in which koji converts starches to sugars, which

happens at the same time that yeast converts sugars to alcohol, is known as ‘multiple-parallel fermentation’, and is unique in sake

production.

Sake rice is far starchier than edible rice. Sake makers are looking for starch content, not nutrients. A grain of sake rice is

larger than table rice and much hardier. Currently, there are roughly 60 varieties of brewing rice commonly used. The most famous

is called Yamada Nishiki. Yamada Nishiki comes from a brewing rice called Omachi, the granddaddy of many of the currently used

varietals. Not every brewery uses it, but instead selects a rice that works best with the available water and for the type of sake the

brewery wants to produce.

After proper sake rice has been secured, it is milled, or polished, to prepare it for brewing good sake. This is not as simple

as it might sound, since it must be done gently so as not to generate too much heat or not to crack the rice kernels. Polishing is a

function of removing the outer layers of rice, which include the fats, proteins, minerals, and vitamins, to reach a more abundant layer

of starch. The machines that do this have vertical pivoted rollers that scrape away layer after layer. A percentage is calculated by the

weight of the removed shavings for each grain of rice. For example, rice that is milled to 60% means that 40% of each grain has

been removed.

This is a very important number in premium sake, because it determines the way that the sake is categorized. The sake

industry uses the polishing rates to define the purity level of each sake. Rice that has been milled to 70% has more of the outside of

each grain than rice that has been polished to 50%; thus the rice with the 50% milling ratio is considered to be the ‘purer’ of the two.

Typically, sake rice that is polished to 50% will require 40 to 50 hours in the milling machine.

161