Page 92 - The Complete Rigger’s Apprentice

P. 92

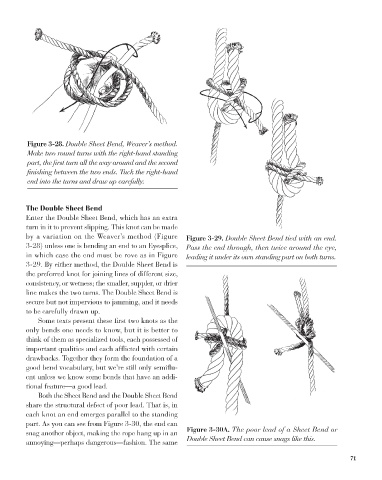

Figure 3-28. Double Sheet Bend, Weaver’s method.

Make two round turns with the right-hand standing

part, the first turn all the way around and the second

finishing between the two ends. Tuck the right-hand

end into the turns and draw up carefully.

The Double Sheet Bend

Enter the Double Sheet Bend, which has an extra

turn in it to prevent slipping. This knot can be made

by a variation on the Weaver’s method (Figure Figure 3-29. Double Sheet Bend tied with an end.

3-28) unless one is bending an end to an Eyesplice, Pass the end through, then twice around the eye,

in which case the end must be rove as in Figure leading it under its own standing part on both turns.

3-29. By either method, the Double Sheet Bend is

the preferred knot for joining lines of different size,

consistency, or wetness; the smaller, suppler, or drier

line makes the two turns. The Double Sheet Bend is

secure but not impervious to jamming, and it needs

to be carefully drawn up.

Some texts present these first two knots as the

only bends one needs to know, but it is better to

think of them as specialized tools, each possessed of

important qualities and each afflicted with certain

drawbacks. Together they form the foundation of a

good bend vocabulary, but we’re still only semiflu-

ent unless we know some bends that have an addi-

tional feature—a good lead.

Both the Sheet Bend and the Double Sheet Bend

share the structural defect of poor lead. That is, in

each knot an end emerges parallel to the standing

part. As you can see from Figure 3-30, the end can

snag another object, making the rope hang up in an Figure 3-30A. The poor lead of a Sheet Bend or

annoying—perhaps dangerous—fashion. The same Double Sheet Bend can cause snags like this.

71