Page 365 - Geosystems An Introduction to Physical Geography 4th Canadian Edition

P. 365

Chapter 11 Climate Change 329

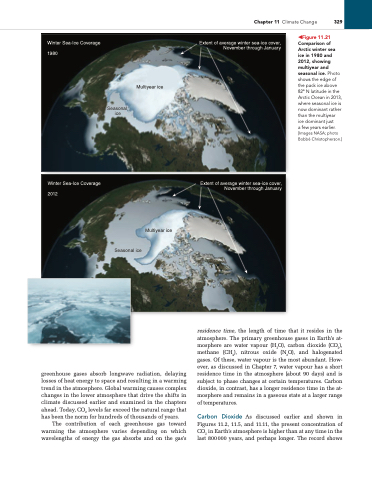

◀Figure 11.21 Comparison of Arctic winter sea ice in 1980 and 2012, showing multiyear and seasonal ice. Photo shows the edge of the pack ice above 82° n latitude in the arctic Ocean in 2013, where seasonal ice is now dominant rather than the multiyear ice dominant just

a few years earlier. [images naSa; photo Bobbé Christopherson.]

Winter Sea-Ice Coverage 1980

Extent of average winter sea-ice cover, November through January

Winter Sea-Ice Coverage 2012

Extent of average winter sea-ice cover, November through January

Seasonal ice

Multiyear ice

Multiyear ice Seasonal ice

greenhouse gases absorb longwave radiation, delaying losses of heat energy to space and resulting in a warming trend in the atmosphere. Global warming causes complex changes in the lower atmosphere that drive the shifts in climate discussed earlier and examined in the chapters ahead. Today, CO2 levels far exceed the natural range that has been the norm for hundreds of thousands of years.

The contribution of each greenhouse gas toward warming the atmosphere varies depending on which wavelengths of energy the gas absorbs and on the gas’s

residence time, the length of time that it resides in the atmosphere. The primary greenhouse gases in Earth’s at- mosphere are water vapour (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and halogenated gases. Of these, water vapour is the most abundant. How- ever, as discussed in Chapter 7, water vapour has a short residence time in the atmosphere (about 90 days) and is subject to phase changes at certain temperatures. Carbon dioxide, in contrast, has a longer residence time in the at- mosphere and remains in a gaseous state at a larger range of temperatures.

Carbon Dioxide As discussed earlier and shown in Figures 11.2, 11.5, and 11.11, the present concentration of CO2 in Earth’s atmosphere is higher than at any time in the last 800000 years, and perhaps longer. The record shows