Page 502 - Geosystems An Introduction to Physical Geography 4th Canadian Edition

P. 502

466 part III The Earth–Atmosphere Interface

F cus Study 15.1environmental Restoration Stream Restoration: Merging Science and Practice

As mentioned in Chapter 1, “basic” science is designed to advance knowledge and build scientific theories. “Applied” science solves real-world problems, and by doing so often advances new technologies and develops natural resource management strategies. Beginning in the late 1980s,

the restoration of rivers and streams has become a focus for both basic and applied geomorphology.

Stream restoration, also called river restoration, is the process that reestab- lishes the health of a fluvial ecosystem, including channel processes and form, riparian vegetation, and fisheries. Every stream restoration project has a particu- lar focus, which varies with the problems and impacts on that particular stream. Common restoration goals are to rein- state instream flows, restore fish passage, prevent bank erosion, and reestablish vegetation along the channel or on the floodplain. The scale of a stream restora- tion varies from a few hundred metres of stream to hundreds of kilometres of river to an entire watershed.

Dam Removals

Dams may be targeted for removal by scientists, government agencies, and environmental groups if they are unsafe or their original purpose is no longer valid. Removal of a dam is intended to allow river discharge patterns, sediment transport, and habitats to return to natural free-flowing conditions.

The Finlayson Dam project on the Big East River in the Muskoka district of On- tario in 2000 marked the first Canadian dam removal that followed an intricately planned process. The goal was habitat restoration to enhance the brook trout fishery; post-project monitoring shows that brook trout have successfully moved into the former reservoir area and that habitat restoration is ongoing. In 1999, Edwards Dam was deconstructed from the Kennebec River in Augusta, Maine, marking the first dam removal in the United States for ecological reasons (primarily to restore passage between the river and sea for migratory fish).

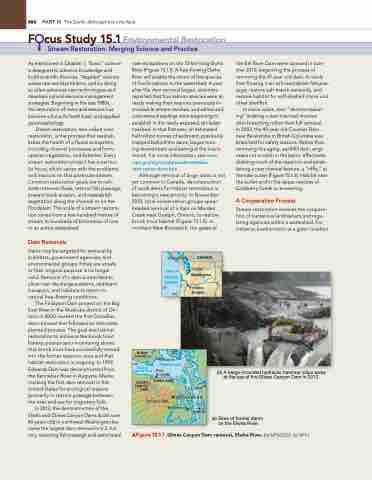

In 2013, the deconstruction of the Elwha and glines Canyon Dams (both over 80 years old) in northwest Washington be- came the largest dam removal in U.S. his- tory, restoring fish passage and associated

river ecosystems on the 72-km-long Elwha River (Figure 15.1.1). A free-flowing Elwha River will enable the return of five species of Pacific salmon to the watershed. A year after the dam removal began, scientists reported that four salmon species were al- ready making their way into previously in- accessible stream reaches, and willow and cottonwood saplings were beginning to establish in the newly exposed, silt-laden riverbed. In that first year, an estimated half million tonnes of sediment, previously trapped behind the dams, began mov- ing downstream and exiting at the river’s mouth. For more information, see www .nps.gov/olym/naturescience/elwha- restoration-docs.htm.

Although removal of large dams is not yet common in Canada, deconstruction of small dams for habitat restoration is becoming a new priority. In november 2010, local conservation groups spear- headed removal of a dam on Marden Creek near guelph, Ontario, to restore brook trout habitat (Figure 15.1.2). In northern new Brunswick, the gates of

the Eel River Dam were opened in sum- mer 2010, beginning the process of removing the 47-year old dam. A newly free-flowing river will reestablish fish pas- sage, restore salt marsh wetlands, and restore habitat for soft-shelled clams and other shellfish.

In some cases, dam “decommission- ing” (making a dam inactive) involves dam breaching rather than full removal. In 2003, the 40-year old Coursier Dam near Revelstoke in British Columbia was breached for safety reasons. Rather than removing this aging, earthfill dam, engi- neers cut a notch in the berm, effectively draining much of the reservoir and estab- lishing a new channel feature, a “riffle,” at the lake outlet (Figure 15.1.3). Habitat near the outlet and in the upper reaches of Cranberry Creek is recovering.

A Cooperative Process

Stream restoration involves the coopera- tion of numerous landowners and regu- lating agencies within a watershed. For instance, bank erosion at a given location

45°

British Columbia

124°

Strait of Juan de Fuca

GLINES CANYON DAM

(b) A barge-mounted hydraulic hammer chips away at the top of the Glines Canyon Dam in 2012.

Vancouver

Elwha R.

PACIFIC OCEAN

125°

123°

Victoria

Puget Sound

Port Angeles

ELWHA DAM

CANADA

Seattle

Washington

Portland

Oregon

48°

Everett

Washington

E

l

w

h

a

R

.

Olympic Mts.

Bremerton

Seattle

(a) Sites of former dams on the Elwha River.

▲Figure 15.1.1 Glines Canyon Dam removal, elwha River. [(a) nPS/USgS. (b) nPS.]