Page 623 - Geosystems An Introduction to Physical Geography 4th Canadian Edition

P. 623

Chapter 18 The Geography of Soils 587

F cus Study 18.1 Pollution

Selenium Concentration in Soils: The Death of Kesterson

About 95% of the irrigated acreage in Canada and the United States lies west of the 98th meridian, a region that is increas- ingly troubled with salinization and water- logging problems. Drainage of agricultural wastewater poses a particular problem in semiarid and arid lands, where river dis- charge is inadequate to dilute and remove field runoff. Fields are often purposely overwatered to keep salts away from the effective rooting depth of the crops. One solution is to place field drains beneath the soil to collect gravitational water

(Figure 18.1.1). But agricultural drain water must go somewhere, and for the San Joaquin Valley of central California, this problem triggered a 25-year controversy surrounding toxic levels of selenium in the wetland ecosystem of kesterson Reservoir.

California’s western San Joaquin Valley is one of at least nine sites in the western United States experiencing contamina- tion from increasing selenium concentra- tions. Selenium is a trace element that occurs naturally in bedrock, particularly Cretaceous shales found throughout

the western United States. Toxic effects of selenium were reported during the 1980s in some domestic animals graz-

ing on grasses grown in selenium-rich soils in the Great Plains. in California, the coastal mountain ranges are a significant source region for selenium. As parent materials weather, selenium-rich alluvium washes into valleys, forming Solonetzic soils (Aridisols in the U.S. Taxonomy) that become productive with the addition of irrigation water. Selenium then becomes

0

Direction of ground- water movement

10 20 KILOMETRES

Proposed extension to the San Francisco Bay N

CALIFORNIA

San Joaquin Valley

Kesterson National Wildlife Refuge

San Luis Drain

Panoche Cr.

Agricultural sub- surface drainage waters transport selenium.

Source of selenium

Cantua Cr.

Map Area

▲Figure 18.1.1 Fields drain into canals. Soil drainage canal collects contaminated water from field drains and directs it into the Salton Sea. Such soil-moisture tile drains and collection channels are used

in the San Joaquin Valley. [Robert Christopherson.]

concentrated by evaporation in farmlands and may become mobilized by irrigation drainage into wetlands, where it bioaccu- mulates to toxic levels.

Central California’s potential drain outlets for agricultural wastewater are lim- ited. yet by the late 1970s a drain about 130 kilometres long was built in the west- ern San Joaquin Valley, without an outlet or the completion of a formal plan. Large- scale irrigation of corporate-owned farms continued, supplying the field drains with salty, selenium-laden runoff that made

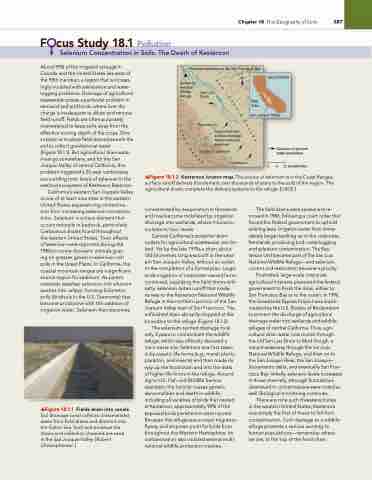

its way to the kesterson National Wildlife Refuge in the northern portion of the San Joaquin Valley east of San Francisco. The unfinished drain abruptly stopped at the boundary to the refuge (Figure 18.1.2).

The selenium-tainted drainage took only 3 years to contaminate the wildlife refuge, which was officially declared a toxic waste site. Selenium was first taken in by aquatic life forms (e.g., marsh plants, plankton, and insects) and then made its way up the food chain and into the diets of higher life forms in the refuge. Accord- ing to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service scientists, the toxicity causes genetic abnormalities and death in wildlife, including all varieties of birds that nested at kesterson; approximately 90% of the exposed birds perished or were injured. Because this refuge was a major migration flyway and stopover point for birds from throughout the Western Hemisphere, its contamination also violated several multi- national wildlife protection treaties.

The field drains were sealed and re- moved in 1986, following a court order that forced the federal government to uphold existing laws. irrigation water then imme- diately began backing up in the corporate farmlands, producing both waterlogging and selenium contamination. The kes- terson Unit became part of the San Luis National Wildlife Refuge—and selenium control and restoration became a priority.

Frustrated, large-scale corporate agricultural interests pressured the federal government to finish the drain, either to San Francisco Bay or to the ocean. in 1996, the Grasslands Bypass Project was imple- mented by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to prevent the discharge of agricultural drainage water into wetlands and wildlife refuges of central California. Thus, agri- cultural drain water now moves through the old San Luis Drain to Mud Slough, a natural waterway through the San Luis National Wildlife Refuge, and then on to the San Joaquin River, the San Joaquin– Sacramento delta, and eventually San Fran- cisco Bay. initially, selenium levels increased in those channels, although fluctuations downward in concentrations were noted as well. Biological monitoring continues.

There are nine such threatened sites in the western United States; kesterson was simply the first of these to fail from contamination. Such damage to a wildlife refuge presents a serious warning to human populations—remember where we are, at the top of the food chain.

▲Figure 18.1.2 Kesterson locator map. The source of selenium is in the Coast Ranges; surface runoff delivers this element over thousands of years to the soils of the region. The agricultural drains complete the delivery systems to the refuge. [USGS.]

a

n

I

J

S

o

a

q

A

u

i

n

R

i

v

N

e

r

J

O

A

Q

U

N

S

G

V

C

A

L

O

A

E

S

Y

T

L

R

A

N

E