Page 12 - Gallery 19C Nazarenes Catalogues

P. 12

a handsomely paid, two-year leave, Carstens had brazenly refused: Swiss heroes, as Lionel Gossman reminds us, or members of the

“I belong not to the Berlin Academy but to all of humanity.” This is, French Revolutionary Assembly—inevitably implied insurrection and

7

how the Viennese art student felt, too. Their own quest for renewal, the rejection of established ways. Part of their gesture’s genuinely

however, carried them not to archaic Greece but the Middle Ages, reformatory quality was the egalitarian, non-hierarchical structure of

which for them had culminated, as the ultimate high- and endpoint of their society, whose members were bound together by a freely taken

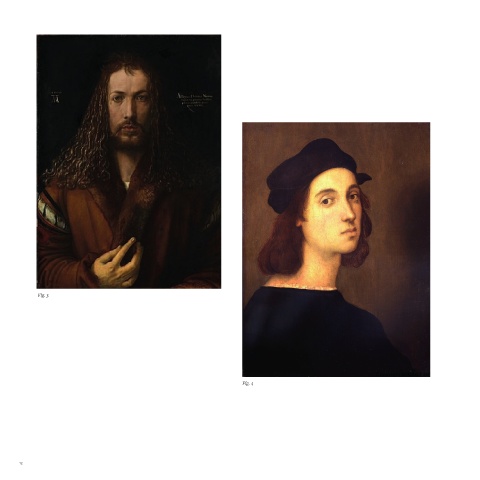

medieval art, in Raphael (1483–1520) and Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). oath rather than the invisible bonds of tradition and history. They

They embodied what their young devotees desired most: a perfect dedicated the newly formed union to the patron saint of painters,

fusion of style, authentic self-expression and heartfelt spirituality (Figs. St. Luke, and from now on called their fraternity der Lukasbund, the

3 and 4). Imagining something of an artistic yin and yang, the young Brotherhood of Saint Luke, and themselves Lukasbrüder, the brethren

painters dreamed to unite the essence of these artists-saints—the ideal of Saint Luke. Their choice of patron affirmed their conviction that

beauty of the South and the Northern penchant for the characteristic— Art must serve only the highest of ends, above all religion, and never

in their own work (Fig. 5). The goal was to marry Italia and Germania, budge to the vanity of courts or wealthy individuals. The otherwise

thus following Dürer on his, as Overbeck put it, “straight simple path grim situation only stoked their determination. The academy had

of nature and truth,” while pursuing Raphael’s perfection, in whom, as been forced to close as a result of the French occupation, and

Schadow added, “the Christian spirit [has] enjoyed the most perfect when it reopened the following winter it admitted, due to limited

outer appearance.” For all his enthusiasm, Schadow was well aware of resources, only Austrian citizens. Sutter was the only one among

8

the gap between dream and reality. “We continually call Raphael,” he his brethren who qualified. Thus excluded, the Lukasbrüder seized

cried out, “but what of Raphael in us? … where a thousand roses bloom the opportunity. On May 15, 1810, exactly a year after Napoleon

for him, hardly a modest bud opens for us.” Fortunately, the Nazarene had entered the Austrian capital, they set out for Rome. With the

9

bouquet would ultimately become rather opulent; but the aspiring founding of a Bund, the freshly minted fraternity had formed one of

artists had to scramble as they embarked on their aesthetic quest. the earliest avant-gardes. With their unsanctioned departure from the

Quite often, Overbeck, among his Viennese cohort the most educated academy, they now made history as the first secession in modern art.

and theologically sophisticated, had to jump in when his comrades

could not get their biblical stories straight, and more than once pencil

and brush did not obey to produce the perfect outlines or finely painted

surfaces they aspired to. But quitting was not an option, and if they

Fig. 3 ever faltered in faith they looked to Job, the biblical incarnation of

perseverance in the face of unjust suffering, to persevere themselves.

The whole episode of a few disgruntled art students might have easily

remained a footnote to art history, had it not been for the next step.

By 1809, Overbeck and Pforr had attracted a small but dedicated

following that represented a cross-section of German youth from

various cities and states, with Joseph Sutter (1781–1866) as the only

Austrian. Konrad Hottinger (1788–1827) was Swabian, while Joseph

Wintergerst (1783–1867) and Ludwig Vogel (1788–1879) both were

Fig. 4

10

Zürich citizens. One warm summer evening in July of that year,

the six took a radical step. Inspired by the first anniversary of their

meetings, they decided to formalize their association by handshake

and solemn oath. This was indeed a revolutionary gesture, at least

in the eyes of a period when oath-swearing—whether by medieval

Fig. 5

Image to be replaced

Fig 4. 12 13