Page 280 - Gulf Precis (III)_Neat

P. 280

104

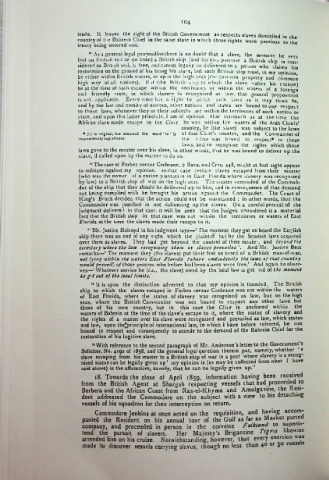

trade. It leaves the right of the British Government as respects slaves domiciled in the

country of the Bahrein Chief in the same state in which those rights were previous to th

treaty being entered into. c

" Asa general legal proposition there is no doubt that a slave, the moment he sets

foot on British soil or on board a British ship (and for this purpose a British ship is con

sidered as British soil, is free, and cannot legally be delivered to a person who claims his

restoration on the ground of his being his slave, but such British ship must, in my opinion

be either within British waters, or upon the high seas (the common property and common

high way of all nations). If it (the British ship to which the slave makes his escape)

be at the time of such escape within the territories or within the waters of a foreign

and friendly state, in which slavery is recognised as law, that general proposition

is not applicable. Every state has a right to adopt such laws as it may think fit,

and hy the law and comity of nations, other nations and states are bound to pay respect

to those laws, whenever they or their subjects arc within the territories of such nation or

slate, and upon this latter principle, l am of opinion that inasmuch as at the time the

African slave made escape to the Clive he was within the waters of the Arab Chiefs'

country, he (the slave) was subject to the laws

• Stc in original, but auumed the word ' lo1 is of that Chief's country, and the Commander of

inadvertently superfluous. the Clive was bound to respect* to those

laws, and to recognise the rights which those

laws gave to the master over his slave, in other words, that he was bound to deliver up the

slave, if called upon by the master to do so.

*' The case of Forbes versus Cochrane, 2 Baru. and Cres. 448, might at first sight appear

to militate against my opinion, in that case certain slaves escaped from their master

(who was the owner of a cotton plantation in East Florida where slavery was recognized

by law) to a British ship of- war on ihe high seas. The master demanded of the Comman

der of the ship that they should be delivered up to him, and in consequence of that demand

not being complied with he brought his action agaiust the Commander. The Court of

King's Bench decided that the action could not be maintained ; in other words, that the

Commander was justified in not delivering up the slaves. On a careful perusal of the

judgment delivered in that case, it will be seen that the Judges considered it a material

fact that the British ship in that case was not within the territories or waters of East

Florida at the time the slaves made their escape to it.

“ Mr. Justice Holroyd in his judgment says—' The moment they got onboard the English

ship there was an end of any right which the plaintiff had by the Spanish laws acquired

over them as slaves. They bad got beyond the control of their master, and beyond the

territory where the law recognising them as slaves prevailed '. And Mr. Justice Best

remarks—* The moment they (the slaves) put their feet on board of a British man-of-war,

not lying within the waters East Florida (where undoubtedly the laws oj that country

would prevail) of those persons who before had been slaves were free.’ And again he obser

ves—{ Whatever service he (».*., the slave) owed by the local law is got rid of the moment

he g't out of the local limits.'

11 It is upon the distinction adverted to that my opinion is founded. The British

ship to which the slaves escaped in Forbes versus Cochrane was not within the waters

of East Florida, where the status of slavery was recognized as law, but on the high

seas, where the British Commander was not bound to respect any other laws but

those of his own country, hut in this case the Clive is anchored within the

waters of Bahrein at the time of the slave’s escape to it, where the status of slavery and

the rights of a master over his slave were recognised and prevailed as law, which status

and law, upon the’principle of international law, to which I have before referred, he was

bound to respect and consequently to accede to the demand of the Bahrein Chief for the

restoration of his fugitive slave.

“With reference to the second paragraph of Mr. Anderson’s letter to the Governments

Solicitor, No. 4190 of 1858, and the general legal question therein put, namely, whether a

slave escaping from his master to a British ship of war in a port where slavery is a recog

nised status can be legally given up* iny opinion is (as may be collected from what I have

said above) in the affirmative, namely, that he can be legally given up.”

18. Towards the close of April 1859, information having been received

from the British Agent at Shargah respecting vessels that had proceeded to

Berbera and the African Coast from Ras-el-Khyma and Amulgavine, the Resi

dent addressed the Commodore on the subject with a view to his detaching

vessels of his squadron for their interception on return.

Commodore Jenkins at once acted on the requisition, and having accom

panied the Resident on his annual tour of the Gulf as far as Maskat parte ^

company, and proceeded in person in the corvette Falkland to superin

tend the pursuit of slavers. Her Majesty's Brigantine Tigris iiKew

attended him on his cruise. Notwithstanding, however, that every exertion * *

made to discover vessels carrying slaves, though no less than 40 or 50 ve