Page 26 - The Ashley Book of Knots

P. 26

-

ON KNOTS

for the left-laid as for the right-laid rope, which suggests that the

latter is more reliable.

The RIGHT OVERHAND BEND O~I4IO) showed a ratio of about two

to three in favor of right-laid rope. An inferior material was used for

these experiments, the excellent material of the earlier experiments

being exhausted, so the actual figures of the experiments are not re-

liable.

To prevent slipping, a knot depends on friction, and to provide

friction there must be pressure of some sort. This pressure and the

place within the knot where it occurs is called the nip. The security

of a knot appears to depend solely on its nip. The so-called and oft-

quoted "principle of the knot," that "no two parts which would

move in the same direction, if the rope were to slip, should lie along-

side of and touching each other," plausible though it may appear,

does not seem important. Even if it were possible to make a knot

conform to any extent to these exacting conditions, it still would

not hold any better than another, unless it were well nipped.

66,67. An excellent example of this is the SHEET BEND. The SHEET

Bnm O~66) violates the alleged "principle" at about every point

where it can, but it has a good nip and does not slip easily. The LEFT-

HAND SHEET BEND (~67) conforms to the so-called "principle" to a

remarkable extent, but has a poor nip and is unreliable.

It does not appear to make much difference just where the nip

within a knot occurs, so far as security is concerned. But the knot

'U)ilt be stronger if the nip is well within the structure.

68. In the ordinary strength test, under a gradually increasing load,

Dr. Cyrus Day found the SHEET BEND and the LEFT-HAND SHEET

BEND about equal.

I tested strength with a series of single jerks of gradually increasing

force.

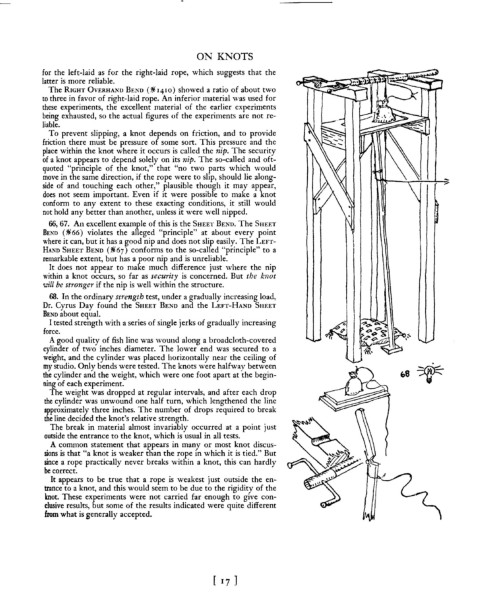

A good quality of fish line was wound along a broadcloth-covered

cylinder of two inches diameter. The lower end was secured to a

weight, and the cylinder was placed horizontally near the ceiling of

my studio. Only bends were tested. The knots were halfway between •

the cylinder and the weight, which were one foot apart at the begin-

ning of each experiment.

The weight was dropped at regular intervals, and after each drop

the cylinder was unwound one half turn, which lengthened the line

approximately three inches. The number of drops required to break

the line decided the knot's relative strength.

The break in material almost invariably occurred at a point just

outside the entrance to the knot, which is usual in all tests.

A common statement that appears in many or most knot discus-

sions is that "a knot is weaker than the rope in which it is tied." But

since a rope practically never breaks within a knot, this can hardly

be correct.

It appears to be true that a rope is weakest just outside the en-

trance to a knot, and this would seem to be due to the rigidity of the

mot. These experiments were not carried far enough to give con-

clusive results, but some of the results indicated were quite different

from what is generally accepted.

[ 17 J