Page 287 - Vol_2_Archaeology of Manila Galleon Seaport Trade

P. 287

15 A Study of the Chinese Influence on Mexican Ceramics 261

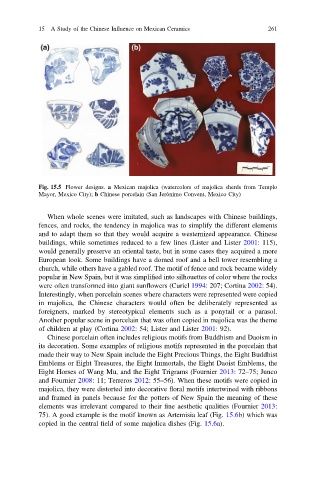

Fig. 15.5 Flower designs. a Mexican majolica (watercolors of majolica sherds from Templo

Mayor, Mexico City); b Chinese porcelain (San Jerónimo Convent, Mexico City)

When whole scenes were imitated, such as landscapes with Chinese buildings,

fences, and rocks, the tendency in majolica was to simplify the different elements

and to adapt them so that they would acquire a westernized appearance. Chinese

buildings, while sometimes reduced to a few lines (Lister and Lister 2001: 115),

would generally preserve an oriental taste, but in some cases they acquired a more

European look. Some buildings have a domed roof and a bell tower resembling a

church, while others have a gabled roof. The motif of fence and rock became widely

popular in New Spain, but it was simpli!ed into silhouettes of color where the rocks

were often transformed into giant sunflowers (Curiel 1994: 207; Cortina 2002: 54).

Interestingly, when porcelain scenes where characters were represented were copied

in majolica, the Chinese characters would often be deliberately represented as

foreigners, marked by stereotypical elements such as a ponytail or a parasol.

Another popular scene in porcelain that was often copied in majolica was the theme

of children at play (Cortina 2002: 54; Lister and Lister 2001: 92).

Chinese porcelain often includes religious motifs from Buddhism and Daoism in

its decoration. Some examples of religious motifs represented in the porcelain that

made their way to New Spain include the Eight Precious Things, the Eight Buddhist

Emblems or Eight Treasures, the Eight Immortals, the Eight Daoist Emblems, the

Eight Horses of Wang Mu, and the Eight Trigrams (Fournier 2013: 72–75; Junco

and Fournier 2008: 11; Terreros 2012: 55–56). When these motifs were copied in

majolica, they were distorted into decorative floral motifs intertwined with ribbons

and framed in panels because for the potters of New Spain the meaning of these

elements was irrelevant compared to their !ne aesthetic qualities (Fournier 2013:

75). A good example is the motif known as Artemisia leaf (Fig. 15.6b) which was

copied in the central !eld of some majolica dishes (Fig. 15.6a).