Page 74 - Tibetan Thangka Painting Methodsand Mat, Jackson

P. 74

The Order of Sketching or flames) and seat for each figure.

When this much of the sketch had been completed

The sequence of sketching in an ordinary thangka it was common for an artist to go back and check the

painting may be summarized as follows. The first step main proportions of each figure. For rapid double-

was the division of the painting surface, and here, as checking some artists compared certain key measures of

already described, one of our informants used ovals to height and breadth of each figure. Lastly, the artist

indicate the places of the main figures. Next the artist surrounded the divine figures with sketches of pleasant

established the lengths of the units of measure to be landscapes or other appropriate surroundings and

used when drawing those particular figures. For a ornamentations. The main features of the standard

Buddha or bodhisattva in a sitting posture the length of landscapes were clouds, mountains, greenery, lakes

one large unit (cha chen) or span worked out at about and waterfalls. The artist drew these working in general

one-eighth of the preliminary oval. For a standing from the top to the bottom of the sketch, and at this

Buddha or bodhisattva the large unit would equal about time he often added some prominent details such as

one-twelfth of the length of the oval. flowers, offerings, auspicious jewels and animals.

When drawing designs that included a main figure

and a surrounding group of lesser figures, a painter had

to establish two scales of measures. From the beginning

he assigned a larger central oval to the main figure and o o

gave the lesser figures correspondingly smaller ovals, o 0

usually from one-half to one-fourth of the length of the

main figure. The artist determined the exact relationship

between these scales of measure according to the

particular exigencies of each composition.

Sometimes the design entailed three or even more

scales of measures: that of a main figure, that of a main

retinue, that of a lesser retinue above or below, and so o o

on. In paintings where the deities had been individually

chosen by the patron or his preceptor, the different

scales of measures usually did not express a priori

hieratic distinctions, but only the main focus and

descending priorities of the particular composition as

determined by the patron or by the lama who originally

advised him to commission the thangka.

In order to establish the values of the main

measures during sketching, the artist usually marked the

actual length of the span (rntho or cha chen) of the main

figure on a splint of wood or bamboo. Often a painter

would further subdivide this homemade "ruler" (thig

shing) into units of six, four, three, two and one sor rno,

since these lengths were needed in constructing the

linear grids or sdom-tshad skeleton lines. The painter 0000

also required separate "rulers" for the lesser scales of

measurement in the design.

The preparation for sketching the main figure

began with the construction of a linear grid - in full or

abbreviated form - to conform with the bodily

dimensions of that deity or guru. For deities with bent

forms, such as goddesses and wrathful figures, the artist

had to fix the angles of the chest and head at an early

stage. Then he could delineate the area of the head with

a rectangle, followed by the drawing of the oval of the

face. Next came the abdomen, followed by the arms

and legs. The sketching of the robes, together with other

garments and ornaments, concluded the initial sketch of

the first figure. After sketching the main figure the artist

proceeded to draw the other figures following the same

basic procedure. Some artists, however, preferred to

sketch all of the measurement grids first, before drawing

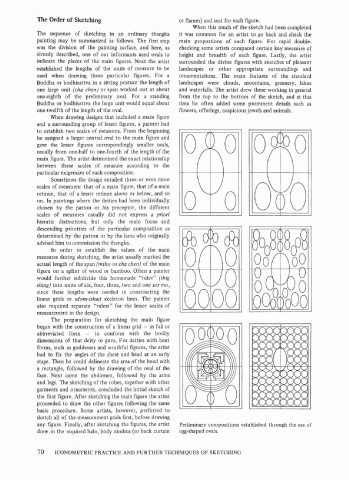

any figure. Finally, after sketching the figures, the artist Preliminary compositions established through the use of

drew in the required halo, body nimbus (or back curtain egg-shaped ovals.

70 ICONOMETRIC PRACTICE AND FURTHER TECHNIQUES OF SKETCHING