Page 78 - Blum Feinstein Tanka collection HIMALAYAN Art Bonhams March 20 2024

P. 78

Sonam Lhundrup was also a prolific author, whose corpus of written works

exceeded more than three hundred titles. His main contributions to Tibetan

Buddhist canon include his commentaries on the major works of Sakya Pandita

(1182-1251), which were held in such high regard that Sonam Lhundrup was

considered to be a later incarnation of this Sakya patriarch. He composed

biographies such as the life of Kunga Wangchuk, histories, praises, and manuals

for rituals and meditative practice. Within the last decade of his life, he would

train many Sakya and Ngor leaders at the threshold of the 16th century, including

the ninth and tenth abbots of Ngor, and continue to teach and write in Lo and its

neighboring kingdoms in the western Himalayas.

As demonstrated by this important commission, the large quantity of portrait

bronzes produced during this exceptional period of Tibetan art history

demonstrates that there were concurrent stylistic preferences for non-gilded

bronzes in Central Tibet, which were frequently being inlaid or heavily patterned.

An overwhelming correlation between portraits representing monastic orders,

especially that of the Sakya, traces the aesthetic preference for non-gilded

images to Mustang, Tsang, and the western half of Central Tibet. In the case

of Sonam Lhundrup, his popular representation among portraits was partly

due to an influx of wealth from the kingdom of Lo’s salt trade. Three high

quality portrait images of smaller scale are in museum collections: one is in

the Philadelphia Museum of Art (2003-6-1); another in the National Museum of

Asian Art, Washington D.C. (S2015.28.8); and a third in the Musée Guimet, Paris

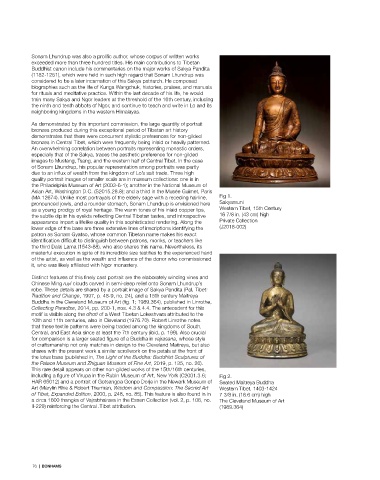

(MA 12674). Unlike most portrayals of the elderly sage with a receding hairline, Fig 1.

pronounced jowls, and a rounder stomach, Sonam Lhundrup is envisioned here Sakyamuni

as a young prodigy of royal heritage. The warm tones of his inlaid copper lips, Western Tibet, 15th Century

the subtle dip in his eyelids reflecting Central Tibetan tastes, and introspective 16 7/8 in. (43 cm) high

appearance impart a lifelike quality in this sophisticated rendering. Along the Private Collection

lower edge of the base are three extensive lines of inscriptions identifying the (J2018-002)

patron as Sonam Gyatso, whose common Tibetan name makes his exact

identification difficult to distinguish between patrons, monks, or teachers like

the third Dalai Lama (1543-88), who also shares this name. Nevertheless, its

masterful execution in spite of its incredible size testifies to the experienced hand

of the artist, as well as the wealth and influence of the donor who commissioned

it, who was likely affiliated with Ngor monastery.

Distinct features of this finely cast portrait are the elaborately winding vines and

Chinese Ming ruyi clouds carved in semi-deep relief onto Sonam Lhundrup’s

robe. These details are shared by a portrait image of Sakya Pandita (Pal, Tibet:

Tradition and Change, 1997, p. 48-9, no. 24), and a 15th century Maitreya

Buddha in the Cleveland Museum of Art (fig. 1; 1989.364), published in Linrothe,

Collecting Paradise, 2014, pp. 200-1, nos. 4.3 & 4.4. The antecedent for this

motif is visible along the dhoti of a West Tibetan Lokeshvara attributed to the

10th and 11th centuries, also in Cleveland (1976.70). Robert Linrothe notes

that these textile patterns were being traded among the kingdoms of South,

Central, and East Asia since at least the 7th century (ibid, p. 199). Also crucial

for comparison is a larger seated figure of a Buddha in vajrasana, whose style

of craftsmanship not only matches in design to the Cleveland Maitreya, but also

shares with the present work a similar scrollwork on the petals at the front of

the lotus base (published in, The Light of the Buddha: Buddhist Sculptures of

the Palace Museum and Zhiguan Museum of Fine Art, 2019, p. 135, no. 26).

This rare detail appears on other non-gilded works of the 15th/16th centuries,

including a figure of Virupa in the Rubin Museum of Art, New York (C2001.3.6; Fig 2.

HAR 65012) and a portrait of Gotsangpa Gonpo Dorje in the Newark Museum of Seated Maitreya Buddha

Art (Marylin Rhie & Robert Thurman, Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art Western Tibet, 1403-1424

of Tibet, Expanded Edition, 2000, p. 248, no. 85). This feature is also found in in 7 3/8 in. (18.6 cm) high

a circa 1600 thangka of Vajrabhairava in the Essen Collection (vol. 2, p. 106, no. The Cleveland Museum of Art

II-229) reinforcing the Central .Tibet attribution. (1989.364)

| BONHAMS

76

76 | BONHAMS