Page 52 - 2019 September 10th Sotheby's Important Chinese Art Jades, Met Museum Irving Collection NYC

P. 52

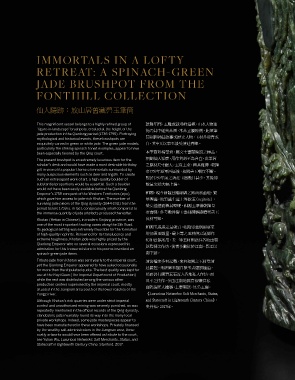

IMMORTALS IN A LOFTY

RETREAT: A SPINACH-GREEN

JADE BRUSHPOT FROM THE

FONTHILL COLLECTION

ẁṢ晙嶉烉㓦Ⱉ⯭冲啷䡏䌱䫮䫺

This magniÞ cent vessel belongs to a highly reÞ ned group of Ḧ昮⸜攻炻䌱晽ㆸ⯙䘣Ⲙ忈㤝炻Ⱉ㯜Ṣ䈑䫮

‘Þ gure-in-landscape’ brushpots, created at the height of the 䫺ᷫ℞ᷕ䴻℠⑩栆炻㛔⑩㬋Ⱄ冣ἳˤ㬌栆䫮

jade production in the Qianlong period (1736-1795). Portraying

mythological and historical events, these brushpots are 䫺⇣∫䤆娙㓭ḳㆾ㬟⎚Ṣ䈑炻䌱㛸⣂⍾曺ㆾ

exquisitely carved in green or white jade. The green jade models, 䘥炻℞ᷕ⍰ẍ䡏䌱㚨⍿㶭⺟曺䜆ˤ

particularly the striking spinach-toned examples, appear to have

㛔䫮䫺䍵䦨厗屜炻Ⱄ㔯⢓㚠敋昛姕ᷳ㤝⑩炻

been especially favored by the Qing court.

⇣∫ẁṢ䤍渧炻䓐ἄ屨⢥军䁢⎰⭄ˤ㬌䫮䫺

The present brushpot is an extremely luxurious item for the

scholar’s desk and would have made a most desirable birthday ᷳ⍇㛸⯢⮠漸⣏炻䌱岒ᶲḀ炻㤝℞暋⼿炻Ḧ昮

gift in view of its popular theme of immortals surrounded by ⷅIJĸĶĺ⸜㳦幵大⼩⼴炻數伶䌱㛅届ᶵ㕟ˤ

many auspicious elements such as deer and lingzhi. To create

墥㕤IJĸĶĺ⸜⇵ᷳ㶭⺟䌱☐㔠䚖䓂⮹炻℞⼴⌣

such an extravagant work of art, a high-quality boulder of

substantial proportions would be essential. Such a boulder 㔠慷䨩䃞⣏ⷭᶲ㎂ˤ

would not have been easily available before the Qianlong

Emperor’s 1759 conquest of the Western Territories (xiyu), 數炻䎦Ṳ㕘䔮㚦Ⱄ䴚䵊ᷳ嶗⓮⊁慵⛘炻䷩

which gave him access to jade-rich Khotan. The number of 厗冰䚃炻⛘岒䚃䓇䓊ᶲ䫱庇䌱炷ůŦűũųŪŵŦ炸炻

surviving jade pieces of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) from the 䐑Ṗ忂德侴㤝℞➭䠔ˤ數䌱㶙⼿Ḧ昮䘯

period before 1759 is, in fact, conspicuously small compared to

the immense quantity of jade artefacts produced thereafter. ⷅ曺䜆炻⍫侫㔠ẞ䡏䌱☐⇣⽉墥娑孂▮伶䌱

Khotan (Hetian in Chinese), in modern Xinjiang province, was 列㛸⎗䞍ˤ

one of the most important trading oases along the Silk Road.

數䌱㬚㬚⭂慷㛅届炻Ḧ昮ⷅ᷎„䇦天㯪

Its geological setting was extremely favorable for the formation

of high-quality nephrite. Renowned for its translucency and ⡆≈届䌱㔠慷ˤ㚨ᶲ䫱ᷳ䌱㛸ὃ⭖⺟⽉ἄ

extreme toughness, Khotan jade was highly prized by the ⛲⤪シ棐䓐炻㫉ᶨ䫱䌱㛸⇯復⼨⎬⛘䓙㛅

Qianlong Emperor who on several occasions expressed his

⺟䚋䜋ᷳἄ⛲炻⼴侭⣂㔠ỵ㕤㰇⋿ˣ攟㰇ẍ

admiration for this treasured stone in his poems inscribed on

spinach-green jade items. ⋿ᶳ㷠ˤ

Tribute jade from Khotan was sent yearly to the imperial court, 㶭⭖㨼㟰⣂㚱姀庱炻Ἦ冒數ᷳ䌱㛸⍿㶭

yet the Qianlong Emperor appeared to have asked occasionally

⺟♜㍏炻㛒䴻⽉㸾㑭冒㍉䌱侭㆚优㤝慵炻

for more than the stipulated quota. The best quality was kept for

use at the Ruyi Guan (The Imperial Department of Production) 䃞侴ṵ㚱⃒岒䌱䞛㳩ℍ⎬⛘䥩Ṣἄ⛲炻侴

while the rest was distributed among the various other ᶼᶵ᷷Ἓἄ炻⣂䓙㰇⋿⛘⋨塽渥⭀䥩

production centers supervised by the imperial court, mostly

冒倀婳⋈Ṣ晽墥炻ᶲ⣱㛅⺟炻夳⏛䌱炻

situated in the Jiangnan area south of the lower reaches of the

Yangzi river. ˪ōŶŹŶųŪŰŶŴġŏŦŵŸŰųŬŴĻġŔŢŭŵġŎŦųŤũŢůŵŴĭġŔŵŢŵŶŴĭġ

Although Khotan’s rich quarries were under strict imperial ŢůťġŔŵŢŵŦŤųŢŧŵġŪůġņŪŨũŵŦŦůŵũġńŦůŵŶųźġńũŪůŢ˫炻

control and unauthorized mining was severely punished, as was ⎚ᷡ䤷炻ijıIJĸ⸜ˤ

repeatedly mentioned in the o' cial records of the Qing dynasty,

clandestine jade invariably found its way into the many local

private workshops. Indeed, some jade masterpieces appear to

have been manufactured in these workshops. Privately Þ nanced

by the wealthy salt administrators in the Jiangnan area, these

costly artworks would have been o# ered as tribute to the court,

see Yulian Wu, Luxurious Networks: Salt Merchants, Status, and

Statecraft in Eighteenth Century China, Stanford, 2017.

50 SOTHEBY’S