Page 200 - Art De' Asie Christie's Paris December 16, 2022

P. 200

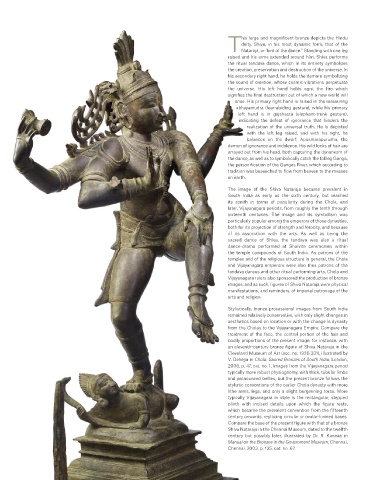

his large and magnificent bronze depicts the Hindu

deity, Shiva, in his most dynamic form, that of the

TNataraja, or ‘lord of the dance.” Standing with one leg

raised and his arms extended around him, Shiva performs

the ritual tandava dance, which in its entirety symbolizes

the creation, preservation and destruction of the universe. In

his secondary right hand, he holds the damaru symbolizing

the sound of creation, whose cosmic vibrations perpetuate

the universe. His left hand holds agni, the fire which

signifies the final destruction out of which a new world will

arise. His primary right hand is raised in the reassuring

abhayamudra (fear-abiding gesture), while his primary

left hand is in gajahasta (elephant-trunk gesture),

indicating the defeat of ignorance that hinders the

realization of the universal truth. He is depicted

with the left leg raised, and with his right, he

balances on the dwarf, Apasmarapurusha, the

demon of ignorance and indolence. His wild locks of hair are

arrayed out from his head, both capturing the dynamism of

the dance, as well as to symbolically catch the falling Ganga,

the personification of the Ganges River, which according to

tradition was beseeched to flow from heaven to the masses

on earth.

The image of the Shiva Nataraja became prevalent in

South India as early as the sixth century, but reached

its zenith in terms of popularity during the Chola, and

later, Vijayanagara periods, from roughly the tenth through

sixteenth centuries. The image and its symbolism was

particularly popular among the emperors of those dynasties,

both for its projection of strength and ferocity, and because

of its association with the arts. As well as being the

sacred dance of Shiva, the tandava was also a ritual

dance-drama performed at Shaivite ceremonies within

the temple compounds of South India. As patrons of the

temples and of the religious structure in general, the Chola

and Vijayanagara emperors were also thus patrons of the

tandava dances and other ritual performing arts. Chola and

Vijayanagara rulers also sponsored the production of bronze

images, and as such, figures of Shiva Nataraja were physical

manifestations, and reminders, of imperial patronage of the

arts and religion.

Stylistically, bronze processional images from South India

remained relatively conservative, with only slight changes in

aesthetics based on location or with the change in dynasty

from the Cholas to the Vijayanagara Empire. Compare the

treatment of the face, the central portion of the hair and

bodily proportions of the present image, for instance, with

an eleventh-century bronze figure of Shiva Nataraja in the

Cleveland Museum of Art (acc. no. 1930.331), illustrated by

V. Dehejia in Chola: Sacred Bronzes of South India, London,

2006, p. 47, cat. no. 1. Images from the Vijayanagara period

typically more robust physiognomy, with thick, tubular limbs

and pronounced bellies, but the present bronze follows the

stylistic conventions of the earlier Chola dynasty with more

lithe arms, legs, and only a slight burgeoning torso. More

typically Vijayanagara in style is the rectangular, stepped

plinth with incised details upon which the figure rests,

which became the prevalent convention from the fifteenth

century onwards, replacing circular or ovular-formed bases.

Compare the base of the present figure with that of a bronze

Shiva Nataraja in the Chennai Museum, dated to the twelfth

century but possibly later, illustrated by Dr. R. Kannan in

Manual on the Bronzes in the Government Museum, Chennai,

Chennai, 2003, p. 135, cat. no. 67.

198 199