Page 139 - The Arts of China, By Michael Sullivan Good Book

P. 139

today very little survives of the great Buddhist architecture,

sculpture, and painting of the seventh and eighth centuries. Again

we must look to Japan, and it is the monasteries at Nara, itself a

replica ofCh'ang-an, that preserve some of the finest of T'ang art.

Todaiji was not an exact copy of a T'ang temple, but in its gran-

deur of scale and conception it was designed to rival the great

Chinese foundations. It was built on a north-south axis with pa-

godas flanking the main approach. A huge gateway leads into a

courtyard dominated by the Buddha Hall (Daibutsuden), 290 feet

long by 170 feet deep by 156 feet high, housing a gigantic seated

Buddha in bronze, consecrated in 752. Much restored and altered,

this is today the largest wooden building in the world, though in

its time the Chien-yiian-tien at Loyang, long since destroyed, was

even larger.

The earliest known T'ang wooden temple building is the small

main hall of Nan-ch'an-ssu in Wu-t'ai-hsien, Shansi, built in 782;

the largest is the main hall of Fu-kuang-ssu on Wu-t'ai-shan, built

in the mid-ninth century. Both of these buildings show a slight

curve in the silhouette of the roof that was to become more pro-

nounced with time and to be a dominant feature of Far Eastern ar-

chitecture. Many theories have been advanced to account for this

curve, the most farfetched being that it was intended to imitate the

sagging lines of the tents used by the Chinese in some long-for-

gotten nomadic stage. But we do not need to look so far afield, for

the curve is inherent in the Chinese roof truss itself. Unlike the

rigid triangular Western truss with its central king post, the

Chinese truss consists of a framework of horizontal beams sup-

ported on queen posts, surmounted by purlins to which the rafters

are fixed. The architect has only to vary the height of the queen

posts to arrive at any contour he desires. It is impossible to sayjust

when this curve began to appear. It is perceptible in the sixth cen-

tury and is used with great delicacy in the Sui, as shown by a beau-

tiful stone sarcophagus of 608 in the Sian Museum. The lift at the

corners, as well as adding to the beauty of the roof, helped to ac-

commodate the extra bracketing required to support the enor-

mous overhang of the eaves at that point.

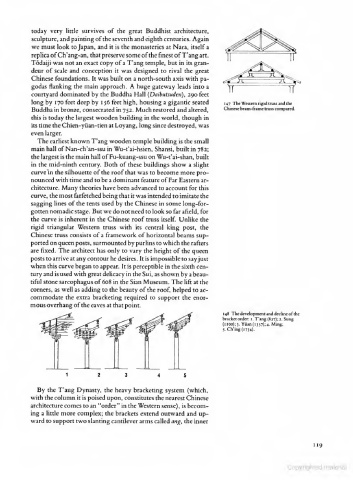

1 48 The development and decline of the

bracket order: I. T'ang (857); 2. !

(1100); 3. Yuan (1357); 4. Ming;

5.Ch'ing(l7J4).

By the T'ang Dynasty, the heavy bracketing system (which,

with the column it is poised upon, constitutes the nearest Chinese

architecture comes to an "order" in the Western sense), is becom-

ing a little more complex; the brackets extend outward and up-

ward to support two slanting cantilever arms called ang, the inner

119

Copyrighted material