Page 18 - 2021 March 16th Indian, Himalayan and Tibetan Art, Bonhams NYC New York

P. 18

The exceptional artist has embedded yet more symbolism into a technical detail

of his creation. The waters brim with additional sprouts creeping over the sides

of the lotus pedestal. The vines perform a structural function by supporting the

figure, who would otherwise be connected to the base only by the weak point of

the left foot. This technical knowhow was commonly employed by Pala artists,

though rarely so elaborately. More often, long trailing scarfs or even a plain stem

at the back were used as supports, as for a Hevajra in the Nyingjei Lam Collection

(Weldon & Casey Singer, Sculptural Heritage of Tibet, London, 1999, p.21, fig.14).

A later Tibetan copy of Vajrayogini in the Pala style shows a simple stem rising from

the top of the base (HAR 57313), and another of Vajravarahi in the Metropolitan

Museum of Art has a more elaborate support rising from the tail of a goose (fig.2;

2014.720.2). Yet, all pale in comparison to the creative vision and technical

prowess exhibited by the variety of flowers reaching upward in celebration of this

Vajravarahi.

The 10th, 11th, and 12th centuries saw a period of religious and artistic transfer

between India and Tibet known as the Second Dissemination of Buddhism in

Tibet. While many sculptures imitating the Pala style were produced in Tibet during

and after the Second Dissemination, the nuance and depth of this Vajravarahi’s

symbolism indicate an original model from Northeastern India. Indeed, the

confident display of the knot tying Vajravarahi’s belt at the small of her back, the

crisp pendants hanging from her necklace, and the lozenges in the bangle around

her left wrist, representing human bone ornaments sometimes used in tantric

rituals, evince the intricate bronze casting of the late Pala period. The insistence

on figural plasticity in India’s material culture is alive in the suppleness of her waist

and hamstrings. Rather than sacrifice a convincing portrayal of her balance in order

to merely accomplish the iconography of her dancing, as is often done in Tibetan

copies (fig.2), the trajectory of sprouting flowers cater to an ideal representation

of her pose. Moreover, whereas Indian religious art aims to entice the deity with a

sensuous body to temporarily inhabit, a Tibetan icon’s sacred energy is provided

by consecrations lodged within it. Therefore, the absence of a consecration plate

underneath the sculpture, or of any indication that it was ever meant to confine

one, is another compelling indicator that the bronze is from Northeastern India.

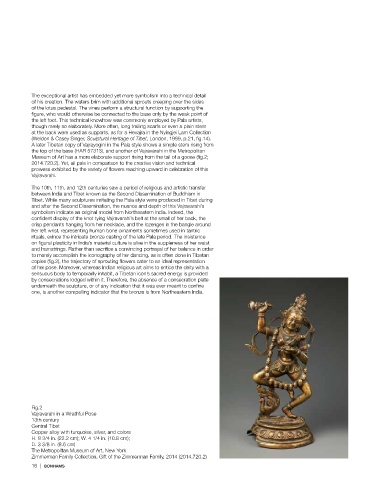

Fig.2

Vajravarahi in a Wrathful Pose

13th century

Central Tibet

Copper alloy with turquoise, silver, and colors

H. 8 3/4 in. (22.2 cm); W. 4 1/4 in. (10.8 cm);

D. 3 3/8 in. (8.6 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Zimmerman Family Collection, Gift of the Zimmerman Family, 2014 (2014.720.2)

16 | BONHAMS