Page 111 - Chinese Art Bonhams San Francisco December 18, 2017

P. 111

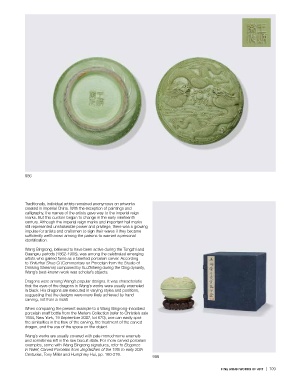

986

Traditionally, individual artists remained anonymous on artworks

created in imperial China. With the exception of paintings and

calligraphy, the names of the artists gave way to the imperial reign

marks. But this custom began to change in the early nineteenth

century. Although the imperial reign marks and important hall marks

still represented unshakeable power and privilege, there was a growing

impulse for artists and craftsmen to sign their wares if they became

sufficiently well known among the patrons to warrant a personal

identification.

Wang Bingrong, believed to have been active during the Tongzhi and

Guangxu periods (1862-1908), was among the celebrated emerging

artists who gained fame as a talented porcelain carver. According

to Yinliuzhai Shuo Ci (Commentary on Porcelain from the Studio of

Drinking Streams) composed by Xu Zhiheng during the Qing dynasty,

Wang’s best-known work was scholar’s objects.

Dragons were among Wang’s popular designs. It was characteristic

that the eyes of the dragons in Wang’s works were usually enameled

in black. His dragons are executed in varying styles and positions,

suggesting that the designs were more likely achieved by hand

carving, not from a mold.

When comparing the present example to a Wang Bingrong-inscribed

porcelain snuff bottle from the Meriem Collection (refer to Christie’s sale

1934, New York, 19 September 2007, lot 670), one can easily spot

the similarities in the flow of the carving, the treatment of the carved

dragon, and the use of the space on the object.

Wang’s works are usually covered with pale monochrome enamels

and sometimes left in the raw biscuit state. For more carved porcelain

examples, some with Wang Bingrong signatures, refer to Elegance

in Relief, Carved Porcelain from Jingdezhen of the 19th to early 20th

Centuries, Tony Miller and Humphrey Hui, pp. 160-276. 986

FINE ASIAN WORKS OF ART | 109