Page 428 - Edo: Art in Japan, 1615–1868

P. 428

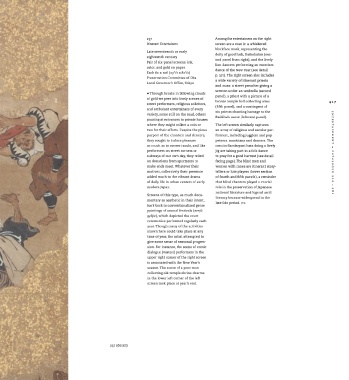

237 Among the entertainers on the right

Itinerant Entertainers screen are a man in a whiskered

blackface mask, representing the

Late seventeenth or early deity of good luck, Daikokuten (sec-

eighteenth century

Pair of six-panel screens; ink, ond panel from right), and the lively

exorcism

lion dancers performing an

color, and gold on paper dance of the New Year (see detail

5

Each 60 x 206 (23 /s x 8iVs)

includes

Preservation Committee of Oba p. 371). The right screen also priests

a wide variety of itinerant

Local Governor's Office, Tokyo

and nuns: a street preacher giving a

sermon under an umbrella (second

• Through breaks in billowing clouds panel), a priest with a picture of a

of gold we peer into lively scenes of bronze temple bell collecting alms

street performers, religious solicitors, 427

and ambulant entertainers of every (fifth panel), and a contingent of

six priests

chanting homage to the

variety, some still on the road, others Buddha's name (leftmost panel).

pausing at entrances to private houses

where they might collect a coin or The left screen similarly captures

two for their efforts. Despite the pious an array of religious and secular per-

purport of the chanters and dancers, formers, including jugglers and pup-

they sought to induce pleasure peteers, musicians and dancers. The

as much as to convert souls, and like men in flamboyant hats doing a lively

performers on street corners or jig are taking part in a folk dance

subways of our own day, they relied to pray for a good harvest (see detail

on donations from spectators to facing page). The blind men and

make ends meet. Whatever their women with canes are itinerant story-

motives, collectively their presence tellers or lute players (lower section

added much to the vibrant drama of fourth and fifth panels), a reminder

of daily life in urban centers of early that blind chanters played a crucial

modern Japan. role in the preservation of Japanese

national literature and legend until

Screens of this type, as much docu- literacy became widespread in the

mentary as aesthetic in their intent,

late Edo period. JTC

hark back to conventionalized genre

paintings of annual festivals (nenjü

gyôjie), which depicted the court

ceremonies performed regularly each

year. Though many of the activities

shown here could take place at any

time of year, the artist attempted to

give some sense of seasonal progres-

sion. For instance, the scene of comic

dialogue (manzai) performers in the

upper right corner of the right screen

is associated with the New Year's

season. The scene of a poor man

collecting old temple shrine charms

in the lower left corner of the left

screen took place at year's end.

237 (detail)