Page 74 - Bonhams March 22 2022 Indian and Himalayan Art NYC

P. 74

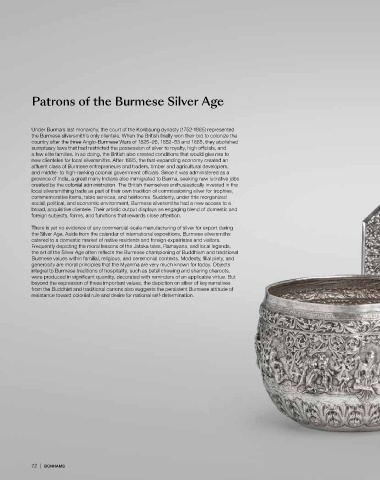

Patrons of the Burmese Silver Age

Under Burma’s last monarchy, the court of the Konbaung dynasty (1752-1885) represented

the Burmese silversmith’s only clientele. When the British finally won their bid to colonize the

country after the three Anglo-Burmese Wars of 1825–26, 1852–53 and 1885, they abolished

sumptuary laws that had restricted the possession of silver to royalty, high officials, and

a few elite families. In so doing, the British also created conditions that would give rise to

new clienteles for local silversmiths. After 1885, the fast-expanding economy created an

affluent class of Burmese entrepreneurs and traders, timber and agricultural developers,

and middle- to high-ranking colonial government officials. Since it was administered as a

province of India, a great many Indians also immigrated to Burma, seeking new lucrative jobs

created by the colonial administration. The British themselves enthusiastically invested in the

local silversmithing trade as part of their own tradition of commissioning silver for trophies,

commemorative items, table services, and heirlooms. Suddenly, under this reorganized

social, political, and economic environment, Burmese silversmiths had a new access to a

broad, acquisitive clientele. Their artistic output displays an engaging blend of domestic and

foreign subjects, forms, and functions that rewards close attention.

There is yet no evidence of any commercial-scale manufacturing of silver for export during

the Silver Age. Aside from the calendar of international expositions, Burmese silversmiths

catered to a domestic market of native residents and foreign expatriates and visitors.

Frequently depicting the moral lessons of the Jataka tales, Ramayana, and local legends,

the art of the Silver Age often reflects the Burmese championing of Buddhism and traditional

Burmese values within familial, religious, and ceremonial contexts. Modesty, filial piety, and

generosity are moral principles that the Myanma are very much known for today. Objects

integral to Burmese traditions of hospitality, such as betel chewing and sharing cheroots,

were produced in significant quantity, decorated with reminders of an applicable virtue. But

beyond the expression of these important values, the depiction on silver of key narratives

from the Buddhist and traditional canons also suggests the persistent Burmese attitude of

resistance toward colonial rule and desire for national self-determination.

72 | BONHAMS