Page 75 - March 23, 2022 Sotheby's NYC Fine Chinese Works of Art

P. 75

The Treaty of Nanjing not only ceded the island of Hong Kong to the British 《南京條約》將香港島割讓予英國,開放五口通

Empire, but it also established five ‘treaty ports’ that lifted trade restric- 商,解除貿易限制,賦予英國貿易特權。五個通商

tions and bestowed privileges upon British merchants: Amoy (Xiamen), 口岸分別為:廈門、廣州、福州、寧波及上海。這

Canton (Guangzhou), Foochow (Fuzhou), Ningpo (Ningbo), and Shanghai. 些地區遂成為傳教士、遊客、外交官、商人、藝術

These areas became commercial centers for missionaries, tourists, dip-

lomats, merchants, artists, and other opportunists who capitalized on 家和其他借人口密度發展的機會主義者們聚集的商

densely populated environments. These areas also proved to be fertile 業溫床。攝影藝術亦在通商口岸藉機流行,隨中國

ground for the spread and adaptation of photography to meet the needs 國人需求及品味適應演變。

and tastes of the Chinese people.

開放新埠通商,機遇隨之而來,然授時局所限,該

The newly established commercial zones created opportunities, but their 時期歷史紀錄缺乏。1850年代,幾位歐美攝影師先

chaotic nature contributed to a lack of historical records. There were sev-

eral European and American photographers active in China by the 1850s, 後活躍於中國,皆暫留數載而後移居他地。當時,

although they did not tend to keep residency for more than a few years 影樓易主後其名號往往被繼承傳用,致使對於新影

before moving on to other markets. When a studio went out of business, 樓的追蹤識別難上加難。直至1860年代初,華人經

it might be pirated by a new owner, making tracking and identification of 營的影樓產業才初具規模,而活躍在1850年代初的

early studios all the more difficult. Chinese-run photographic studios did 眾多華人攝影師的名字卻早已消逝在歷史長河之

not operate in any significant numbers until the early 1860s, and while

Chinese photographers were no doubt plentiful by the early 1850s, their 中。中國第一位職業攝影師傳爲羅元佑,然而其畢

names are lost to history. Lo Yuanyou was perhaps China’s first commer- 生作品竟無一得以傳世。

cial photographer, although nothing remains of his life’s work.

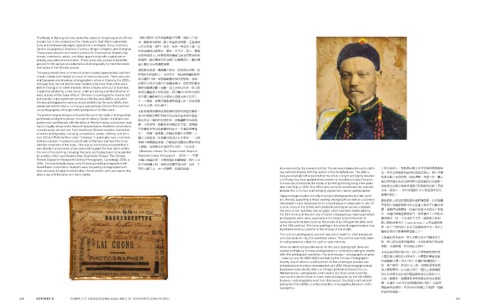

本幅肖像照的精神及風格映射著時代的歷史轉折。

The present daguerreotype embodies the spirit and style of photographic 東方的傳統及喜好與西方的品味及資本發生碰撞,

portraiture during this pivotal moment in history. Eastern traditions and 結合形成了獨特的表現形式。此類攝影作品從構

preferences synthesized with the influx of Western tastes and money, lead- 圖、人物姿勢、服飾及家具陳設各方面,都明顯

ing to a highly idiosyncratic form of representation. Aesthetic conventions

conspicuously carried over from traditional Chinese ancestor portraiture 可見傳統祖先肖像畫審美的影子。學者伍美華指

to studio photography, including composition, poses, clothing, and furni- 出:“所謂「畫得像」的概念其實十分局限,只

ture. Scholar Roberta Wue notes ‘“Likeness,” in particular, was a narrowly 關注人物面部,而身體其他部分並不重要……人物

defined concept. It centered specifically on the face and had little to do 面部由專職藝匠所畫,其餘包括身體及背景則命他

with the remainder of the body…This was so commonly accepted that it 人繪製,這種做法在當時司空見慣。(伍美華,

was standard practice for a face specialist to paint the face alone and for

the rest of the painting, including the body and background, to be painted 《Essentially Chinese: The Chinese Portrait Subject in

by another artist‘ (see Roberta Wue, Essentially Chinese: The Chinese Nineteenth-Century Photography》,頁268 )。早期

Portrait Subject in Nineteenth-Century Photography, Cambridge, 2005, p. 中國人像攝影師,多數遵循此構圖傳統。相片大多

268). Compositionally, many early Chinese portrait photographers fol- 從正面拍攝人物,面部及身體筆直向前,而非一手

lowed these conventions. Subjects were frequently photographed with 置於大腿之上,另一臂微彎,從側面刻畫。 As evidenced by the present portrait, the anti-naturalism of Ko-Lin’s cloth- 正如本品所示,僧格林沁親王身穿衣袍刻畫風格抽

face and body straight-forward rather than in profile, with one hand in the ing contrasts heavily with the realism of his facial features. The sitter’s 象,與其寫實風格的面部形成强烈對比。相片中僧

sitter’s lap and the other arm bent slightly. face, purposefully left unpainted by the artist, is bright and highly detailed. 格林沁親王面容明亮,細節清晰,未經上色。麗昌

Lai Chong may have applied white powder to his subject’s face; this prac- 攝影師在攝影前或為僧格林沁面部塗抹白色脂粉;

tice was documented in the studio of Lai Afong in Hong Kong a few years

later (see Wue, p. 269). This effect only serves to accentuate the contrast 如此做法在數年後被香港黎芳照相館所記錄(見伍

between Ko-Lin’s face and his highly pigmented, heavily-painted jacket. 美華,頁269),旨在增强相片中人物面容與彩色

Daguerreotype studios not only employed photographers but also paint- 服裝的對比。

ers, thereby appealing to those seeking photographs as well as customers 銀版攝影工作室除攝影師外還聘請畫師,以求兼顧

interested in more traditional forms of portraiture in watercolor or oils. Of 喜愛相片和偏愛傳統水彩及油畫人像的不同顧客群

course, many of the artists were skilled in painting on various materials

like ivory or silk, but likely also on glass, which had been fashionable by 體。畫師們技藝精湛,除善於在象牙及絹本上作畫

the 18th century in the port city of Canton (Guangzhou). Hand-pigmented 外,亦懂得玻璃畫繪製技巧,後者曾在十八世紀的

photographs were rarely seen before the advent and proliferation of 廣州風行一時。十九世紀下半葉,諸如黎芳照相

cartes-de-visite studios (such as the studio of Lai Afong in the latter part 館之類的肖像名片(cartes-de-visite)工作室蓬勃發

of the 19th century). The hand-painting in the present daguerreotype may 展,而手工著色照片在此之前則極爲罕見。本品手

have been done by a painter in the employ of the studio.

繪部份或出自影樓所聘畫師之手。

The cost of a photographic portrait was out of reach for most individuals

and attainable for only the wealthiest sitters. This portrait was likely taken 人像攝影成本高昂,對大多數人而言乃屬奢侈之

for self-promotion, either for a gift or aide-mémoire. 物,唯有達官貴族負擔得起。本品應是為自我宣傳

While no direct comparable exists for this early photograph, there are 而攝,或為贈禮,亦或為紀念留影。

several portraits by Chinese photographers in collections dating to shortly 本品並無同期作例可比,但有少許稍後時期的華

after this photograph was taken. Two ambrotypes – photographs on glass 人攝影師人像作品可作參考。中國攝影學會收藏

– taken by Luo Yili (1802-1852) are held by the Chinese Photographic

Society, one of which is a self-portrait. As the ambrotype process was 有兩幅羅以禮(1802-1852)拍攝的玻璃版照片,

not patented and widely disseminated until 1854, the photographs must 其一為自拍照。然1854 年之前,玻璃版照相技術

have been made shortly after Lai Chong’s portrait of General Ko-Lin. 尚未獲取專利,亦未廣泛流行,因此上述玻璃版

Mathematician, cartographer and inventor Zou Boqi constructed his 照片作品應完成於此件麗昌僧格林沁肖像照不久

own camera and is known to have made photographs by the late 1840s; 之後。數學家、製圖師兼發明家鄒伯奇曾自製相

however, no photographs exist from that period. Zou Boqi’s self-portrait,

dating from the 1860s, is in the collection of Guangzhou Museum of Art, 機,並傳於 1840 年代後期開始相片製作,但該時

Guangzhou 期並無作品傳世,其1860年代所攝之自拍照,現藏

於廣州美術館。

146 SOTHEBY’S COMPLETE CATALOGUING AVAILABLE AT SOTHEBYS.COM/N10917 147