Page 8 - Sept 2020

P. 8

In fact, the heavy gold bricks mined, formed, and

shipped south were generally transported in basic canvas

sacks on the floor of small planes, like Wardair’s Beavers

and Otters throughout the 1950s. Noticing this early into

his tenure in the north, Gregson quickly devised a plan

using specially designed canvas bags made by a

seamstress from Edmonton and $30.30 in lead from a

caretaker at the Negus Mines in Yellowknife. Using a lead

brick purchased from a foundry for $25, he was easily

able to make a second brick from the clandestine Negus

Lead Bricks: Worth Their Weight in lead the same size and shape as the gold he targeted.

Gold!

Written by Jenna Greig. Pictures by Nicholas Mather

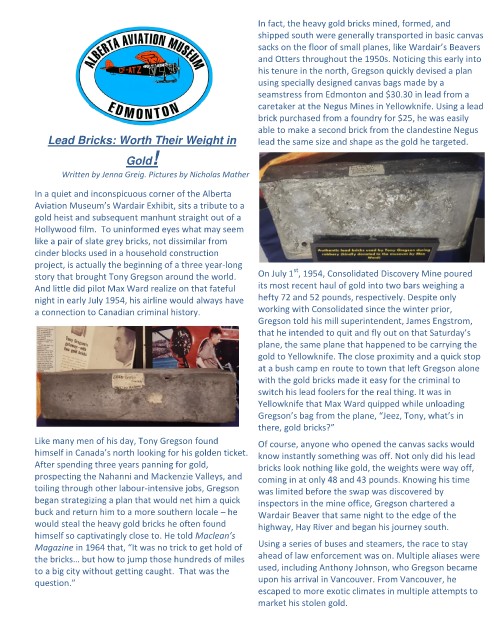

In a quiet and inconspicuous corner of the Alberta

Aviation Museum’s Wardair Exhibit, sits a tribute to a

gold heist and subsequent manhunt straight out of a

Hollywood film. To uninformed eyes what may seem

like a pair of slate grey bricks, not dissimilar from

cinder blocks used in a household construction

project, is actually the beginning of a three year-long

st

story that brought Tony Gregson around the world. On July 1 , 1954, Consolidated Discovery Mine poured

And little did pilot Max Ward realize on that fateful its most recent haul of gold into two bars weighing a

night in early July 1954, his airline would always have hefty 72 and 52 pounds, respectively. Despite only

a connection to Canadian criminal history. working with Consolidated since the winter prior,

Gregson told his mill superintendent, James Engstrom,

that he intended to quit and fly out on that Saturday’s

plane, the same plane that happened to be carrying the

gold to Yellowknife. The close proximity and a quick stop

at a bush camp en route to town that left Gregson alone

with the gold bricks made it easy for the criminal to

switch his lead foolers for the real thing. It was in

Yellowknife that Max Ward quipped while unloading

Gregson’s bag from the plane, “Jeez, Tony, what’s in

there, gold bricks?”

Like many men of his day, Tony Gregson found Of course, anyone who opened the canvas sacks would

himself in Canada’s north looking for his golden ticket. know instantly something was off. Not only did his lead

After spending three years panning for gold, bricks look nothing like gold, the weights were way off,

prospecting the Nahanni and Mackenzie Valleys, and coming in at only 48 and 43 pounds. Knowing his time

toiling through other labour-intensive jobs, Gregson was limited before the swap was discovered by

began strategizing a plan that would net him a quick inspectors in the mine office, Gregson chartered a

buck and return him to a more southern locale – he Wardair Beaver that same night to the edge of the

would steal the heavy gold bricks he often found highway, Hay River and began his journey south.

himself so captivatingly close to. He told Maclean’s

Magazine in 1964 that, “It was no trick to get hold of Using a series of buses and steamers, the race to stay

ahead of law enforcement was on. Multiple aliases were

the bricks… but how to jump those hundreds of miles

used, including Anthony Johnson, who Gregson became

to a big city without getting caught. That was the

question.” upon his arrival in Vancouver. From Vancouver, he

escaped to more exotic climates in multiple attempts to

market his stolen gold.