Page 781 - The Toxicology of Fishes

P. 781

Ecological Risk Assessment 761

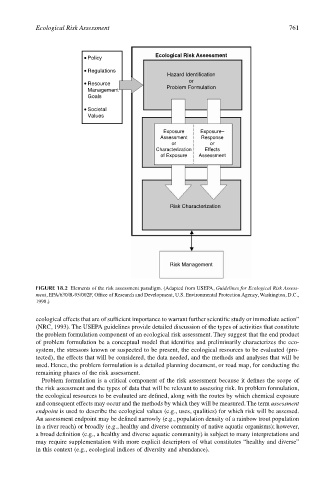

Ecological Risk Assessment

Policy

Regulations

Hazard Identification

or

Resource

Problem Formulation

Management

Goals

Societal

Values

Exposure Exposure–

Assessment Response

or or

Characterization Effects

of Exposure Assessment

Risk Characterization

Risk Management

FIGURE 18.2 Elements of the risk assessment paradigm. (Adapted from USEPA, Guidelines for Ecological Risk Assess-

ment, EPA/630/R-95/002F, Office of Research and Development, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C.,

1998.)

ecological effects that are of sufficient importance to warrant further scientific study or immediate action”

(NRC, 1993). The USEPA guidelines provide detailed discussion of the types of activities that constitute

the problem formulation component of an ecological risk assessment. They suggest that the end product

of problem formulation be a conceptual model that identifies and preliminarily characterizes the eco-

system, the stressors known or suspected to be present, the ecological resources to be evaluated (pro-

tected), the effects that will be considered, the data needed, and the methods and analyses that will be

used. Hence, the problem formulation is a detailed planning document, or road map, for conducting the

remaining phases of the risk assessment.

Problem formulation is a critical component of the risk assessment because it defines the scope of

the risk assessment and the types of data that will be relevant to assessing risk. In problem formulation,

the ecological resources to be evaluated are defined, along with the routes by which chemical exposure

and consequent effects may occur and the methods by which they will be measured. The term assessment

endpoint is used to describe the ecological values (e.g., uses, qualities) for which risk will be assessed.

An assessment endpoint may be defined narrowly (e.g., population density of a rainbow trout population

in a river reach) or broadly (e.g., healthy and diverse community of native aquatic organisms); however,

a broad definition (e.g., a healthy and diverse aquatic community) is subject to many interpretations and

may require supplementation with more explicit descriptors of what constitutes “healthy and diverse”

in this context (e.g., ecological indices of diversity and abundance).