Page 1594 - Clinical Small Animal Internal Medicine

P. 1594

1532 Section 13 Diseases of Bone and Joint

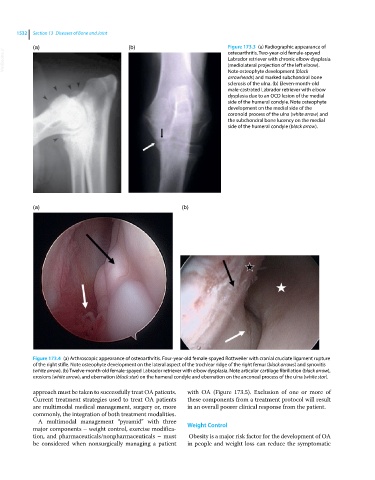

(a) (b) Figure 173.3 (a) Radiographic appearance of

VetBooks.ir Labrador retriever with chronic elbow dysplasia

osteoarthritis. Two‐year‐old female‐spayed

(mediolateral projection of the left elbow).

Note osteophyte development (black

arrowheads) and marked subchondral bone

sclerosis of the ulna. (b) Eleven‐month‐old

male‐castrated Labrador retriever with elbow

dysplasia due to an OCD lesion of the medial

side of the humeral condyle. Note osteophyte

development on the medial side of the

coronoid process of the ulna (white arrow) and

the subchondral bone lucency on the medial

side of the humeral condyle (black arrow).

(a) (b)

Figure 173.4 (a) Arthroscopic appearance of osteoarthritis. Four‐year‐old female‐spayed Rottweiler with cranial cruciate ligament rupture

of the right stifle. Note osteophyte development on the lateral aspect of the trochlear ridge of the right femur (black arrows) and synovitis

(white arrow). (b) Twelve‐month‐old female‐spayed Labrador retriever with elbow dysplasia. Note articular cartilage fibrillation (black arrow),

erosions (white arrow), and ebernation (black star) on the humeral condyle and ebernation on the anconeal process of the ulna (white star).

approach must be taken to successfully treat OA patients. with OA (Figure 173.5). Exclusion of one or more of

Current treatment strategies used to treat OA patients these components from a treatment protocol will result

are multimodal medical management, surgery or, more in an overall poorer clinical response from the patient.

commonly, the integration of both treatment modalities.

A multimodal management “pyramid” with three

major components – weight control, exercise modifica- Weight Control

tion, and pharmaceuticals/nonpharmaceuticals – must Obesity is a major risk factor for the development of OA

be considered when nonsurgically managing a patient in people and weight loss can reduce the symptomatic