Page 14 - Luke AFB Thunderbolt 11-6-15

P. 14

Nov. 6, 2015 Thunderbolt

http://www.luke.af.mil

14 www.aerotechnews.com/lukeafb

by Senior Airman

DEVANTE WILLIAMS

56th Fighter Wing Public Affairs

Retired Chief Master Sgt. Harold

Bergbower was born May 11, 1920,

in Newton, Illinois. He joined the

Army Air Corps May 12, 1939. One

year later, he went to school at Cha-

nute Field, Illinois, and became an

air mechanic. In January 1940, he

volunteered to go to the Philippines

and stayed there for a year and a

half. Everything was good until

Dec. 8, 1941.

“We just got word that Pearl

Harbor was bombed,” he said. “We

also heard that Clark Field had

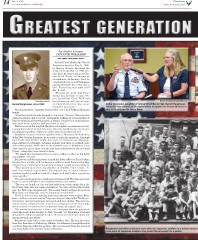

Courtesy photo been bombed as well, but we were Senior Airman Devante Williams

Harold Bergbower, circa 1940 on Clark Field at the time, so we Debra Grunwald, daughter of retired Chief Master Sgt. Harold Bergbower,

holds the microphone for her father when he spoke at a Focus 56 event in

thought it was a joke.” May 2014 on Luke Air Force Base.

Ten minutes later, Japanese bombers flew over Clark Field and dropped C

bombs.

“After the first few bombs dropped, it was silent,” he said. “Seconds later

came the impact, and I was hit. I remember waking up in the morgue at

Fort Stotsenburg, about 80 km north of Manila. I crawled out of the morgue,

went back to my squadron and went back to duty.”

While he was in the hospital, Bergbower’s original squadron moved out,

leaving him behind. It took him more than two months to be returned to

his original squadron, which was miles away from where he was.

Bergbower found out that his squadron was at Mindanao. With the help

of the 26th Cavalry Regiment, he was able to rejoin his squadron. Although

they fought with all their might, they were not victorious over the Japa-

nese and had to surrender. Japanese soldiers took them to a prison camp

called Malaybalay, which was in the northern part of Mindanao. They

were there for about three months and then transferred to Davao Penal

Colony, where they were forced to farm.

“We raised rice and learned how to use a caribou to plow in the fields

and paddies,” he said.

Bergbower and other prisoners farmed the fields of Davao Penal Colony

for about four months until the Japanese soldiers moved them to what they

referred to as a “hell ship” and sent them to Japan to work as slave laborers.

“They packed us in that ship shoulder to shoulder, front to back,” he

said. “You couldn’t even sit down. The ship ride was all a blur. I don’t re-

member anything until we landed in Japan, and that’s when everything

came together.”

The unit was dropped at a warehouse to be hosed off. The Japanese took

them to a steel mill where they worked until the war ended.

“The way we found out the war had ended was when people from the

Red Cross came into our camp and told us. ‘We have entered the atomic

age,’ the Red Cross member said. ‘The atomic bomb had been dropped on

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the Japanese surrendered.’”

The U.S. won the war, and the American prisoners were set free. Berg-

bower and his crew were sent to Tokyo on a hospital ship called The Rescue

where they received treatment, hot meals and new clothes. The unit was

able to send a telegram home. It went to a telegraph service in Canada

where it was then delivered to his parents’ house by regular mail.

“My mother had received a letter and a telegram from the president

about the death of her son Dec. 8, 1941,” he said. “It’s September 1945 and

she gets this telegram saying I’m alive. Of course she went into shock, but

the doctor took care of her.”

Bergbower came back to the states in October 1945. He took the train

from San Francisco to Galesburg, Illinois, to Letterman General Hospital

and from there he called his parents. He was released from the hospital

and went back to his parents’ home in Decatur. Bergbower and other prisoners were taken by Japanese soldiers to a prison camp ca

rows point to Japanese soldiers who joined the prisoners for a photo.