Page 78 - American Stories, A History of the United States

P. 78

The directors of the Dutch West India Com-

pany sponsored two small outposts, Fort Orange 2.1

(Albany), located well up the Hudson River, and N E W F R A N C E

Abenaki

New Amsterdam (New York City) on Manhat- Lake

tan Island. The first Dutch settlers were salaried Champlain 2.2

employees, not colonists, and their superiors in

Europe expected them to spend most of their time NEW Connecticut R.

gathering furs. They did not receive land for their Lake Ontario YORK N.H. 2.3

troubles. Needless to say, this arrangement attracted Mahican

few Dutch immigrants. Iroquois Confederation Albany

The colony’s European population may have MASS. 2.4

been small—only 270 in 1628—but its ethnic mix Lake Erie Susquehanna R.

was extraordinary. One visitor to New Amsterdam Hudson R. CONN.

in 1644 maintained he had heard “eighteen differ- Delaware R.

ent languages” spoken there. Even if this report was PENNSYLVANIA

exaggerated, there is no doubt the Dutch colony Delaware New York

drew English, Finns, Germans, and Swedes. By the (Lenni-Lenape) EAST JERSEY

1640s, a sizable community of free blacks (prob- Germantown

Philadelphia

ably former slaves who had gained their freedom Susquehannock WEST ATLANTIC

through self-purchase) had developed in New MD. JERSEY OCEAN

Amsterdam, adding African tongues to the cacoph-

ony of languages. New England Puritans who left VA. THREE COUNTIES

OF DELAWARE

Massachusetts and Connecticut to stake out farms 0 50 100 miles

on eastern Long Island further fragmented the col- 0 50 100 kilometers

ony’s culture.

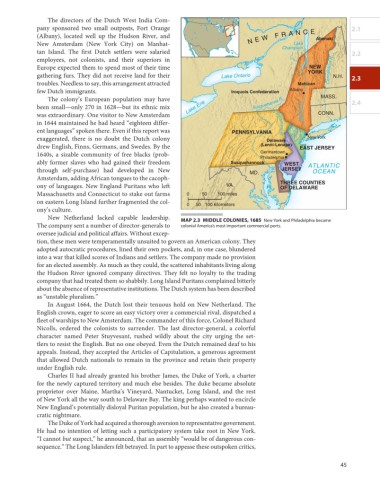

New Netherland lacked capable leadership. map 2.3 middLE CoLoniES, 1685 New York and Philadelphia became

The company sent a number of director-generals to colonial America’s most important commercial ports.

oversee judicial and political affairs. Without excep-

tion, these men were temperamentally unsuited to govern an American colony. They

adopted autocratic procedures, lined their own pockets, and, in one case, blundered

into a war that killed scores of Indians and settlers. The company made no provision

for an elected assembly. As much as they could, the scattered inhabitants living along

the Hudson River ignored company directives. They felt no loyalty to the trading

company that had treated them so shabbily. Long Island Puritans complained bitterly

about the absence of representative institutions. The Dutch system has been described

as “unstable pluralism.”

In August 1664, the Dutch lost their tenuous hold on New Netherland. The

English crown, eager to score an easy victory over a commercial rival, dispatched a

fleet of warships to New Amsterdam. The commander of this force, Colonel Richard

Nicolls, ordered the colonists to surrender. The last director-general, a colorful

character named Peter Stuyvesant, rushed wildly about the city urging the set-

tlers to resist the English. But no one obeyed. Even the Dutch remained deaf to his

appeals. Instead, they accepted the Articles of Capitulation, a generous agreement

that allowed Dutch nationals to remain in the province and retain their property

under English rule.

Charles II had already granted his brother James, the Duke of York, a charter

for the newly captured territory and much else besides. The duke became absolute

proprietor over Maine, Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket, Long Island, and the rest

of New York all the way south to Delaware Bay. The king perhaps wanted to encircle

New England’s potentially disloyal Puritan population, but he also created a bureau-

cratic nightmare.

The Duke of York had acquired a thorough aversion to representative government.

He had no intention of letting such a participatory system take root in New York.

“I cannot but suspect,” he announced, that an assembly “would be of dangerous con-

sequence.” The Long Islanders felt betrayed. In part to appease these outspoken critics,

45