Page 657 - Environment: The Science Behind the Stories

P. 657

drinking water supplies for many communities. Smaller-scale

leaching of toxic materials also occurs, as it is often difficult to

properly line and maintain large impoundments.

We also mine nonmetallic minerals

and fuels

We also mine and use many minerals that do not contain met-

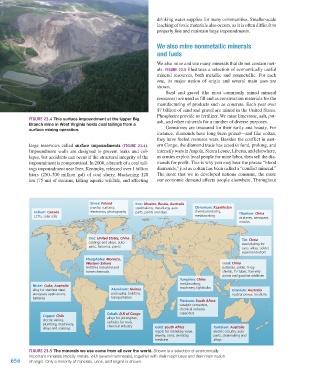

als. Figure 23.5 illustrates a selection of economically useful

mineral resources, both metallic and nonmetallic. For each

one, its major nation of origin and several main uses are

shown.

Sand and gravel (the most commonly mined mineral

resources) are used as fill and as construction materials for the

manufacturing of products such as concrete. Each year over

$7 billion of sand and gravel are mined in the United States.

Phosphates provide us fertilizer. We mine limestone, salt, pot-

Figure 23.4 This surface impoundment at the Upper Big ash, and other minerals for a number of diverse purposes.

Branch mine in West Virginia holds coal tailings from a

surface mining operation. Gemstones are treasured for their rarity and beauty. For

instance, diamonds have long been prized—and like coltan,

they have fueled resource wars. Besides the conflict in east-

large reservoirs called surface impoundments (Figure 23.4). ern Congo, the diamond trade has acted to fund, prolong, and

Impoundment walls are designed to prevent leaks and col- intensify wars in Angola, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and elsewhere,

lapse, but accidents can occur if the structural integrity of the as armies exploit local people for mine labor, then sell the dia-

impoundment is compromised. In 2000, a breach of a coal tail- monds for profit. This is why you may hear the phrase “blood

ings impoundment near Inez, Kentucky, released over 1 billion diamonds,” just as coltan has been called a “conflict mineral.”

liters (250–300 million gal) of coal slurry, blackening 120 The more that we in developed nations consume, the more

km (75 mi) of streams, killing aquatic wildlife, and affecting our economic demand affects people elsewhere. Throughout

Silver: Poland Iron: Ukraine, Russia, Australia

jewelry, currency, steelmaking, metallurgy, auto Chromium: Kazakhstan

Indium: Canada electronics, photography parts, paints and dyes chemical industry, Titanium: China

LCDs, solar cells metalworking airplanes, aerospace,

missiles

Zinc: United States, China Tin: China

coatings and alloys, auto steel plating for

parts, batteries, paints cans, alloys, solder,

superconductors

Phosphates: Morocco,

Western Sahara Lead: China

fertilizer, industrial and batteries, solder, X-ray

home chemicals shields, TV tubes, formerly

paints and gasoline additives

Tungsten: China

metalworking,

Nickel: Cuba, Australia machinery, lightbulbs

alloy for stainless steel, Aluminum: Guinea Uranium: Australia

aerospace applications, packaging, building, nuclear power, medicine

batteries transportation

Platinum: South Africa

catalytic converters,

chemical industry,

Cobalt: D.R of Congo capacitors

Copper: Chile alloys for jet engines,

electric wiring,

plumbing, machinery, carbides for tools,

chemical industry

alloys and coatings Gold: South Africa Tantalum: Australia

ingots for monetary value, electric circuitry, auto

jewelry, coins, dentistry, parts, steelmaking and

medicine alloys

Figure 23.5 The minerals we use come from all over the world. Shown is a selection of economically

important minerals (mostly metals, with several nonmetals), together with their major uses and their main nation

656 of origin. Only a minority of minerals, uses, and origins is shown.

M23_WITH7428_05_SE_C23.indd 656 13/12/14 11:29 AM