Page 687 - Environment: The Science Behind the Stories

P. 687

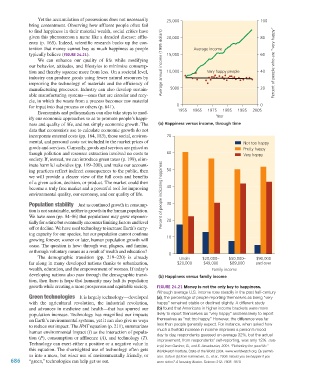

Yet the accumulation of possessions does not necessarily 25,000 100

bring contentment. Observing how affluent people often fail

to find happiness in their material wealth, social critics have

given this phenomenon a name like a dreaded disease: afflu- 20,000 80

enza (p. 165). Indeed, scientific research backs up the con-

tention that money cannot buy as much happiness as people Average Income

typically believe (Figure 24.21). 15,000 60

We can enhance our quality of life while modifying

our behavior, attitudes, and lifestyles to minimize consump- Average annual income (1995 dollars) Percent of people who are ”very happy“

tion and thereby squeeze more from less. On a societal level, 10,000 Very happy people 40

industry can produce goods using fewer natural resources by

improving the technology of materials and the efficiency of

manufacturing processes. Industry can also develop sustain- 5000 20

able manufacturing systems—ones that are circular and recy-

cle, in which the waste from a process becomes raw material

for input into that process or others (p. 641). 0 0

Economists and policymakers can also take steps to mod- 1955 1965 1975 1985 1995 2005

ify our economic approaches so as to promote people’s happi- Year

ness and quality of life, and not simply economic growth. The (a) Happiness versus income, through time

data that economists use to calculate economic growth do not

incorporate external costs (pp. 164, 183), those social, environ- 70

mental, and personal costs not included in the market prices of Not too happy

goods and services. Currently, goods and services are priced as Pretty happy

though pollution and resource extraction involved no costs to 60 Very happy

society. If, instead, we can introduce green taxes (p. 199), elim-

inate harmful subsidies (pp. 199–200), and make our account-

ing practices reflect indirect consequences to the public, then 50

we will provide a clearer view of the full costs and benefits

of a given action, decision, or product. The market could then

become a truly free market and a powerful tool for improving 40

environmental quality, our economy, and our quality of life. Percent of people indicating happiness

Population stability Just as continued growth in consump- 30

tion is not sustainable, neither is growth in the human population.

We have seen (pp. 84–86) that populations may grow exponen-

tially for a time but eventually encounter limiting factors and level 20

off or decline. We have used technology to increase Earth’s carry-

ing capacity for our species, but our population cannot continue

growing forever; sooner or later, human population growth will 10

cease. The question is how: through war, plagues, and famine,

or through voluntary means as a result of wealth and education? 0

The demographic transition (pp. 219–220) is already Under $20,000– $50,000– $90,000

far along in many developed nations thanks to urbanization, $20,000 $49,000 $89,000 and over

wealth, education, and the empowerment of women. If today’s Family income

developing nations also pass through the demographic transi- (b) Happiness versus family income

tion, then there is hope that humanity may halt its population

growth while creating a more prosperous and equitable society. Figure 24.21 Money is not the only key to happiness.

Although average U.S. income rose steadily in the past half-century

Green technologies It is largely technology—developed (a), the percentage of people reporting themselves as being “very

with the agricultural revolution, the industrial revolution, happy” remained stable or declined slightly. A different study

and advances in medicine and health—that has spurred our (b) found that Americans in higher income brackets were more

population increase. Technology has magnified our impacts likely to report themselves as “very happy” and less likely to report

on Earth’s environmental systems, yet it can also give us ways themselves as “not too happy.” However, the difference was far

to reduce our impact. The IPAT equation (p. 211), summarizes less than people generally expect. For instance, when asked how

human environmental impact (I) as the interaction of popula- much a fivefold increase in income improves a person’s mood

day to day, respondents guessed on average 32%, but the actual

tion (P), consumption or affluence (A), and technology (T).

Technology can exert either a positive or a negative value in improvement, from respondents’ self-reporting, was only 12%. Data

in (a) from Gardner, G., and E. Assadourian, 2004. “Rethinking the good life.”

this equation. The shortsighted use of technology often gets Worldwatch Institute, State of the World 2004. www.worldwatch.org. By permis-

us into a mess, but wiser use of environmentally friendly, or sion. Data in (b) from Kahneman, D., et al., 2006. Would you be happier if you

686 “green,” technologies can help get us out. were richer? A focusing illusion. Science 312: 1908–1910.

M24_WITH7428_05_SE_C24.indd 686 13/12/14 10:40 AM