Page 114 - J. C. Turner "History and Science of Knots"

P. 114

104 History and Science of Knots

Other evidence also leads to the conclusion that knots were cherished as an

essential part of everyday life. As a matter of fact, Chinese gentlemen of the

Chou Dynasty (1122-221 B.c.) carried a special tool tied to their waist sashes,

known as hsi. Made of ivory, jade, or bone, the hsi was a device to untie knots.

By the end of the 1st century, Shuang-ch'ien Chieh had met with wide

popularity, as had the Niu-ko Chieh and Ping Chieh. In the early part of the

5th century, a multitude of structurally sophisticated variants of the Shuang-

ch'ien design emerged. The development of Chinese knotwork reached its

first peak during the Sui and T'ang Dynasties (581-907), during which many

innovative forms emerged. A survey of some of the paintings that depict court

life of the period and the practice of decorating the tombs of palace maids

with knots indicates that the art was very much favored by members of the

imperial family. The Ch'ing Dynasty (1644-1911) witnessed yet another state

of prominence in the history of Chinese knotwork. The forms that are basic

to us today, along with their more structurally complex variants, were widely

employed. In fact, the art of knotwork was so popular that even the author

of the Hung-lou Meng, or The Dream of the Red Chamber, made references

to such knots as I chu-hsiang (Incense), Hsiang-yen-k'uai (Elephant's Eye),

Fang-sheng (Twin Diamonds), Ch'ao-t'ien-teng (Sunflower), Mei-hua (Plum

Blossom), and Liu-hs (Willow Leaf).

Some of the finest pieces in the collection of the National Palace Museum

are furnished with decorative knots of the Ch'ing era.

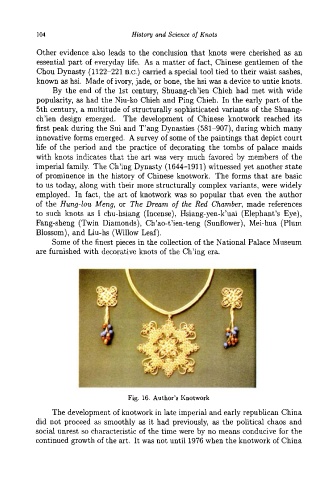

Fig. 16. Author's Knotwork

The development of knotwork in late imperial and early republican China

did not proceed as smoothly as it had previously, as the political chaos and

social unrest so characteristic of the time were by no means conducive for the

continued growth of the art. It was not until 1976 when the knotwork of China