Page 71 - AI WEIWEI CAHIERS D ART

P. 71

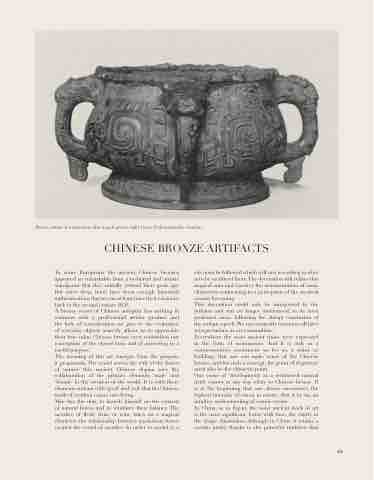

Bronze patina of watermelon skin in pale green. eight: 19 cm. Euformopoulos, London

CHINESE BRONZE ARTIFACTS

To some Europeans the ancient Chinese bronzes appeared so remarkable from a technical and artistic standpoint that they initially refuted their great age. But since then, there have been enough historical authentications that we can at least trace their existence back to the second century BCE.

A bronze vessel of Chinese antiquity has nothing in common with a professional artistic product and the lack of consideration we give to the evaluation of everyday objects scarcely allows us to appreciate their true value. Chinese bronze even contradicts our conception of the closed form and of answering to a useful purpose.

The meaning of this art emerges from the purpose it propounds. The vessel serves the cult of the forces of nature; this ancient Chinese dogma sees the collaboration of the primary elements ‘male’ and ‘female’ in the creation of the world. It is with these elements and not with ‘good’ and ‘evil’ that the Chinese myth of creation comes into being.

Man has the duty to launch himself on the current of natural forces and to reinforce their balance. The sacrifice of flesh, fruit, or wine takes on a magical character; the relationship between mysterious forces created the vessel of sacrifice. In order to model it, a

rite must be followed which will vary according to what is to be sacrificed there. The decoration still relates this magical aura and involves the ornamentation of runic characters conforming to a perception of the mystical cosmic becoming.

This decoration could only be interpreted by the initiates and was no longer understood, in its most profound sense, following the abrupt conclusion of the archaic epoch. We can assuredly renounce all later interpretations as over-naturalistic.

Everywhere the most ancient times were expressed in the form of monuments. And it is only as a commemorative monument (as for us, a statue or building) that one can make sense of the Chinese bronze, and for such a concept, the point of departure must also be the climactic point.

Our sense of ‘development’ as a reinforced natural truth cannot in any way relate to Chinese bronze. It is at the beginning that one always encounters the highest intensity of vision in nature, that is to say, an intuitive understanding of cosmic events.

In China, as in Egypt, the most ancient work of art is the most significant. Later, with time, the clarity in the shape diminishes, although in China it retains a certain purity thanks to the powerful tradition that

63