Page 72 - AI WEIWEI CAHIERS D ART

P. 72

64

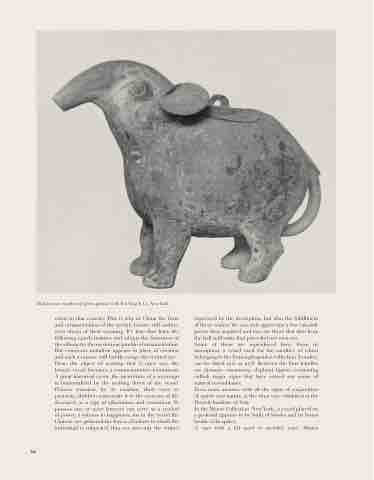

Dark bronze, touches of green patina. Coll. Ton Ying & Co. New York

exists in that country. This is why in China the form and ornamentation of the archaic bronze still endure, even shorn of their meaning. It’s true that later, the following epoch imitates and adopts the heaviness of the silhouette, the mysterious jumble of ornamentation. But conscious imitation appears in place of creation and such a nuance will hardly escape the trained eye. From the object of worship that it once was, the bronze vessel becomes a commemorative monument. A great historical event, the investiture of a sovereign is immortalized by the melting down of the vessel. Princes transmit, by its creation, their vows to posterity; children consecrate it to the memory of the deceased, as a sign of admiration and veneration. To possess one or more bronzes can serve as a symbol of power, a witness to happiness, for in the vessel the Chinese see gathered the forces of nature to which the individual is subjected, they see not only the wishes

expressed by the inscription, but also the fulfillment of these wishes. We can only appreciate a few valuable pieces thus acquired and rare are those that date from the half millennia that preceded our own era.

Some of those are reproduced here. From its inscription, a vessel used for the sacrifice of wheat belonging to the Eumorphopoulos collection (London) can be dated 1105 or 1078. Between the four handles are dynamic ornaments, elephant figures containing cultish magic signs that have erased any sense of natural resemblance.

Even more ancient, with all the signs of conjuration of spirits and nature, is the wine vase exhibited at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

In the Moore Collection (New York), a vessel placed on a pedestal appears to be built of blocks and its forms bristle with spikes.

A vase with a lid used to sacrifice wine (Musée