Page 956 - SUBSEC October 2017_Neat

P. 956

- 3 -

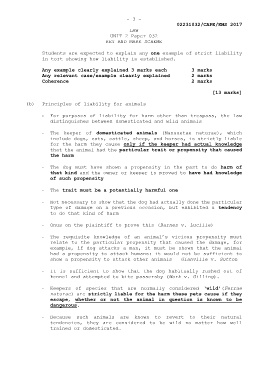

02231032/CAPE/KMS 2017

LAW

UNIT 2 Paper 032

KEY AND MARK SCHEME

Students are expected to explain any one example of strict liability

in tort showing how liability is established.

Any example clearly explained 3 marks each 3 marks

Any relevant case/example clearly explained 2 marks

Coherence 2 marks

[13 marks]

(b) Principles of liability for animals

- For purposes of liability for harm other than trespass, the law

distinguishes between domesticated and wild animals

- The keeper of domesticated animals (Mansuetae naturae), which

include dogs, cats, cattle, sheep, and horses, is strictly liable

for the harm they cause only if the keeper had actual knowledge

that the animal had the particular trait or propensity that caused

the harm

- The dog must have shown a propensity in the past to do harm of

that kind and the owner or keeper is proved to have had knowledge

of such propensity

- The trait must be a potentially harmful one

- Not necessary to show that the dog had actually done the particular

type of damage on a previous occasion, but exhibited a tendency

to do that kind of harm

- Onus on the plaintiff to prove this (Barnes v. Lucille)

- The requisite knowledge of an animal’s vicious propensity must

relate to the particular propensity that caused the damage, for

example, if dog attacks a man, it must be shown that the animal

had a propensity to attack humans: it would not be sufficient to

show a propensity to attack other animals – Glanville v. Sutton

- It is sufficient to show that the dog habitually rushed out of

kennel and attempted to bite passersby (Work v. Gilling).

- Keepers of species that are normally considered ‘wild’(Ferrae

naturae) are strictly liable for the harm these pets cause if they

escape, whether or not the animal in question is known to be

dangerous.

- Because such animals are known to revert to their natural

tendencies, they are considered to be wild no matter how well

trained or domesticated.