Page 100 - The Art & Architecture of the Ancient Orient_Neat

P. 100

■ w

THE BEGINNINGS OF ASSYRIAN ART

planning is, nevertheless, revealing. While the A ssur Ziggurat stood alone, and the Sin-

Shamash temple and the Nabu temple were without towers, the Anu-Adad temple con

sisted of two identical shrines, placed side by side between two square Ziggurats. In all

these temples there was a narrow, deep cella opening from a broad, shallow room, as

we find later in Khorsabad (Figure 30). In the Sin-Shamash temple the two shrines

faced one another across an intervening square court; in the Anu-Adad temple19 they

were placed side by side, separated by a narrow passage. It is clear that many experiments

in the combination of architectural units were made during this time, and it is, therefore,

all the more likely that the differences between Assyrian and Babylonian architecture

are due to intentional innovations on the part of the Assyrians.

We know nothing of the elevations of these Ziggurats, except that contemporary seal

engravings show four or five stages decorated with recesses.20 The temples, too, were

depicted on seals. In figure 24B, we sec two towers flanking the entrance which shows

an altar placed inside; it is shaped like that of our plate 73 b. The figure of a dog which it

supports in figure 24B may be the emblem of the goddess Gula, a form of the Mother

Goddess. The temple shown in figure 32A was probably dedicated to Ea, since his em

blem, the goatfish, surviving as our Capricorn, flanks the entrance. We cannot say, of

course, whether it was carved in stone or cast in bronze or rendered in glazed bricks, but

the designs are valuable sources of our knowledge of Middle Assyrian architecture: they

prove that crenellations crowned the walls and towers, which were decorated with the

usual recesses. Once more the perennial preoccupation with drought is betrayed: above

the shrine clouds are seen from which rain descends on either side.

I have described the scanty remains of the Middle Assyrian Period in some detail, be

cause it was an epoch of artistic energy upon which the subsequent development was

founded. All the distinctive features of Assyrian art were given shape in the last centuries

of the second millennium b.c. But the only monuments which adequately reveal the

v •

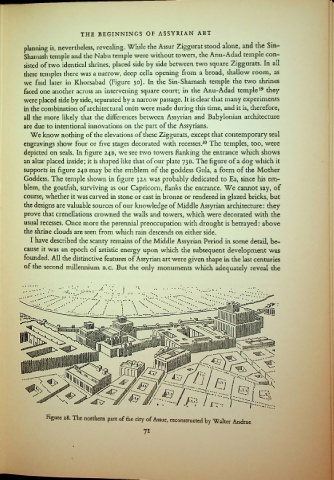

Figure 28. The northern part of the city of Assur, reconstructed by Walter Andrae

71