Page 132 - The Art & Architecture of the Ancient Orient_Neat

P. 132

THE LATE ASSYRIAN PERIOD

of the Mesopotamians. The small bronze of plate ii8b, a truly sickening monstrosity,

fiercely alive, shows that the Assyrians had lost none of this power.

The lampstand (if it is such)59 on plate 117 stands midway between the two other

objects. The figure is hardly ornamentalized. It stands upon a column base of the north

Syrian type used also in Assyrian architecture for porticoes (Figure 35). The three legs

consist of ducks* heads and bulls’ hoofs. This combination of heterogeneous elements is

well in keeping with the baroque richness of the furniture illustrated in the reliefs. The

feet of the lampstand show that the ‘zoomorphic juncture’ which was to play so im

portant a part in Scythian art was known in Assyria; it was also known in the kingdom

i !

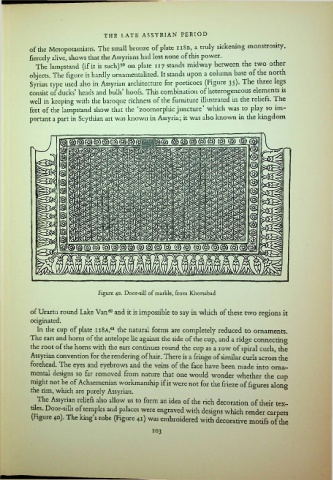

Figure 40. Door-sill of marble, from Khorsabad

of Urartu round Lake Van60 and it is impossible to say in which of these two regions it

originated.

In the cup of plate ii8a,61 the natural forms are completely reduced to ornaments.

The ears and horns of the antelope lie against the side of the cup, and a ridge connecting

the root of the horns with the ears continues round the cup as a row of spiral curls, the

Assyrian convention for the rendering of hair. There is a fringe of similar curls across the

forehead. The eyes and eyebrows and the veins of the face have been made into orna-

mental designs so far removed from nature that one would wonder whether the cup

might not be of Achaemenian workmanship if it were not for the frieze of figures alono-

the rim, which are purely Assyrian.

The Assyrian reliefs also allow us to form an idea of the rich decoration of their tex-

tUes. Door-sills of temples and palaces were engraved with designs which render carpets

(Figure 40). The king's robe (Figure 41) was embroidered with decorative motifs of the

103