Page 187 - The Art & Architecture of the Ancient Orient_Neat

P. 187

PART TWO: THE PERIPHERAL

REGIONS

msmm

K /<

jal ?!

a**''

W>’.' i:

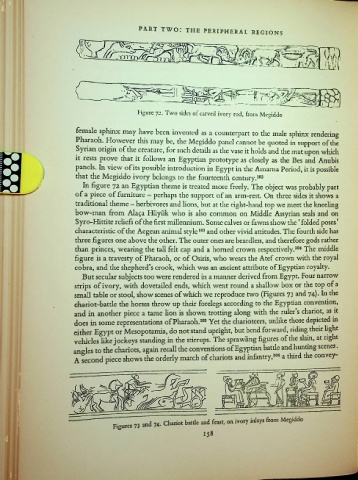

Figure 72. Two sides of carved ivory rod, from Megiddo

female sphinx may have been invented as a counterpart to the male sphinx rendering

Pharaoh. However this may be, the Megiddo panel cannot be quoted in support of the

Syrian origin of the creature, for such details as the vase it holds and the mat upon which

it rests prove that it follows an Egyptian prototype as closely as the Bes and Anubis

panels, hi view of its possible introduction in Egypt in the Amarna Period, it is possible

that the Megiddo ivory belongs to the fourteenth century. 102

/ hi figure 72 an Egyptian theme is treated more freely. The object was probably part

of a piece of furniture - perhaps the support of an arm-rest. On three sides it shows a

traditional theme - herbivores and Hons, but at die right-hand top we meet the kneeling

bow-man from Ala$a Hiiyiik who is also common on Middle Assyrian seals and on

Syro-Hittite rchefs of the first millennium. Some calves or fawns show the ‘ folded poses*

characteristic of the Aegean animal style103 and other vivid attitudes. The fourth side has

three figures one above the other. The outer ones are beardless, and therefore gods rather

than princes, wearing the tall felt cap and a homed crown respectively.104 The middle

figure is a travesty of Pharaoh, or of Osiris, who wears the Atef crown with the royal

cobra, and the shepherd’s crook, which was an ancient attribute of Egyptian royalty.

But secular subjects too were rendered in a manner derived from Egypt. Four narrow

strips of ivory, with dovetailed ends, which went round a shallow box or the top of a

small table or stool, show scenes of which we reproduce two (Figures 73 and 74). hi the

chariot-battle the horses throw up their forelegs according to the Egyptian convention,

and in another piece a tame Hon is shown trotting along with the ruler’s chariot, as it

does in some representations of Pharaoh.105 Yet the charioteers, unHke those depicted in

either Egypt or Mesopotamia, do not stand upright, but bend forward, riding their Hght

vehicles like jockeys standing in the stirrups. The sprawHng figures of the slam, at right

angles to the chariots, again recall the conventions of Egyptian battle and hunting scenes.

A second piece shows the orderly march of chariots and infantry,106 a third the convey-

fgaji la c?

and 74. Chariot battle and feast, on ivory inlays from Megiddo

Figures 73

158